Peter Davison

Peter Davison was Artistic Consultant to Manchester’s Bridgewater Hall from 1994-2018, where he created a high-quality classical music programme without the assistance of direct subsidy. As artistic director of the hall’s International Concert Series, he hosted many prestigious performers such as the Vienna Philharmonic, the Concertgebouw, the Chicago Symphony, as well as soloists such as Lang Lang, Jessye Norman and Cecilia Bartoli. During that time, he was responsible for Pulse; a festival of rhythm and percussion for the Commonwealth Games in 2002, while in 2006, he worked with pianist, Barry Douglas and BBC Radio 3 to stage all Mozart’s piano concertos in five days. In 2012, he collaborated with pianist Noriko Ogawa and the BBC Philharmonic to create Reflections on Debussy, an eight-concert series exploring oriental influence on the French composer.

Until 2014, Peter Davison was artistic director of the Two Rivers Festival in Wirral commissioning several new works and developing acclaimed programmes. He has also lectured in Arts Management at the University of Manchester and the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama. In 2001, he edited Reviving the Muse, a book about the future of musical composition, and in 2010 published Wrestling with Angels about the life and work of Gustav Mahler to accompany The Bridgewater Hall’s acclaimed symphony cycle. He is a renowned Mahler scholar who has spoken at Symposia in Paris (1989), Liverpool (1990) and Boulder, Colorado in 2016 and 2019. He also contributed to Henri Louis de la Grange’s 75th birthday Festschrift, Neue Mahleriana.

Peter Davison created Helios Associates in 1994, an arts management consultancy working with many cultural organisations. He provided financial analysis for the English regional orchestras and assessed major grant-applications for the Arts Council of England involving The Sage, Gateshead, Colston Hall, Bristol, The Hall for Cornwall in Truro, the Watford Palace Theatre, The Arvon Foundation and the London Symphony Orchestra among others. Peter Davison has an M.Phil. in Musicology from the University of Cambridge.

Peter Davison presented this paper at MahlerFest XXXIII. In it, he explores Mahler’s pathway to artistic maturity through the prism of his first major song cycle, Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer) and related works.

The Sorrows of Young Gustav:

Mahler’s Songs of a Wayfarer

by Peter Davison

The young Gustav Mahler

Presented at the Colorado MahlerFest Symposium

Saturday 18 May 2019

Today I am going to explore the origins of Mahler’s first song cycle, the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen or Songs of a Wayfarer. It may appear obvious to state that a conventional musical analysis could never do justice to these extraordinarily intense lyric masterpieces. They tell us so much about the character of Gustav Mahler as a young man. Written when he was still in his early twenties, they reveal in forensic detail the stormy complexities of the composer’s inner life. Not only that, the Songs of a Wayfarer also provide the musical and psychological seeds for Mahler’s First Symphony, and we should consider these works intimately bound. But we shall begin by listening to music conceived when Mahler was just eighteen years old:

The Queen lies on the ground;

The trumpets and drums fall silent.

With horror the knights and damsels flee,

The ancient walls are falling!

The lights are extinguished in the King’s hall

What’s become of the wedding feast?

Ah, sorrow![i]

I. Mahler the wounded boy

The apocalyptic conclusion of Mahler’s early cantata, Das klagende Lied or The Song of Lamentation, depicts the disruption of the nuptial festivities of a royal couple. The palace walls collapse as a great lie is exposed. A troubadour fashions a bone he has found in the forest into a flute. When played, the instrument sings with the voice of the dead youth to whom the bone belonged. He laments to the assembled company that he was killed by his brother who stands ready to marry the very same queen who had created the rivalry between them.

It is no coincidence that a wandering musician – a wayfaring journeyman perhaps – is the messenger of this uncomfortable truth. The moral force of the tale belongs to the wandering musician and the victim-brother who combine to relate a story that shatters outward appearances. They give voice to the wounded Mahler; the Bohemian Jew who felt thrice homeless and who had already known intense personal sorrow, even before he had reached adulthood. In April 1875, just a few months prior to Mahler’s arrival in Vienna to begin his musical studies, his much-loved younger brother Ernst had died from heart disease[ii], aged just 13. Mahler’s grief and perplexity would find expression in the bleak story of Das klagende Lied, which he began composing three years later.

Mahler would have felt considerable guilt as the surviving elder sibling, singled out to achieve greatness, while his brother lay buried in an obscure churchyard. In that sense, Mahler can be identified with the ruthlessly ambitious brother in the story of Das klagende Lied. We cannot escape Mahler’s contradictions. Seeking power and status, Mahler was willing to inflict damage upon himself and others to achieve his aspirations. His warring personality, moving between extreme opposites, infused everything he undertook, and the principal characters of Das klagende Lied represent the conflicting aspects of the Mahlerian psyche. He is the murderer and the murdered, the minstrel who gives voice to truth, the disembodied voice of his own lost innocence and the tyrant who wants to conquer the musical world. Mahler was all of these, and we know from his letters that, during his early adulthood, he often felt marginalised, while his fractured and fractious temperament led to him to suffer bouts of depression and emotional instability. In a letter of 1879, he revealed suicidal feelings to his old schoolfriend, Josef Steiner:

Oh, my beloved earth, when, oh when wilt thou take the abandoned one unto thy breast? Behold! Mankind has banished him from itself, and he flees from its cold and heartless bosom to thee, to thee! Oh, care for the lonely one, for the restless one, Universal Mother!

And then later, Mahler confesses more details of his divided personality:

‘…the highest ecstasy of the most joyous strength of life and the most burning desire for death: these two reign alternately within my heart; yes, oftentimes they alternate within an hour…’

This juxtaposition of extreme contrasts of emotion would become imprinted on Mahler’s musical style. Yet, for all that these passionate statements indicate a young man’s unrequited longing, they also demonstrate a poetic way of being in the world which would shape Mahler’s aesthetics for the rest of his life. His first song cycle, the Songs of a Wayfarer, revels in disjointed and intense emotions, which are only resolved in the serenity of death and dissolving into Nature. Thirty years later, these same sentiments would inspire his musical masterpiece, Das Lied von der Erde, The Song of the Earth.

We might reasonably ask whether Mahler’s youthful intensity was entirely genuine, or whether he exaggerated his feelings to suit the theatricality of the romantic style. As a German-speaking man, born in 1860, Mahler’s affinity with and knowledge of Romanticism from a young age can be safely assumed, allowing him to develop a capacity for hypersensitivity and vivid fantasy. He was steeped in the fairy tales of the Grimm Brothers and the medieval folk poems of Des Knaben Wunderhorn, which fed his appetite for magic, humour and grotesquery. Mahler would also have known the extravagant dream-like novels of Jean Paul Richter and Josef von Eichendorff. But the father figure of the German romantic movement, who was also its most perceptive critic, was Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832), and Mahler found Goethe’s intellectual curiosity and truth-seeking a compelling model for his own artistic projects.

To comprehend more fully Mahler’s psycho-cultural conditioning as a young man, the most important text for consideration is Goethe’s novella, Die Leiden des Jungen Werthers, The Sorrows of Young Werther. The book, which was published in 1774, describes the life and death of a young man who lives according to the highest ideals of morality, love and beauty. His doomed relationship with his beloved Charlotte, whom he places on a pedestal, eventually leads him to kill himself. He cannot bear that, despite their ardent feelings, she will never be free to marry him. In its day, the novel was condemned as a threat to public morals, and it created an enduring cult of the melancholy youth, which reputedly provoked a spate of copy-cat suicides.

Then Werther was not the first such melancholy youth to have entered the literary imagination. Goethe would have known Shakespeare’s Hamlet, another sensitive soul who felt it necessary to pose the ultimate question – to be or not to be? Hamlet contemplates suicide, but it is his beloved Ophelia who drowns herself because she believes her lover to be mad. In a striking parallel with the plot of Das klagende Lied, the play hinges on the murder of one brother by another who seeks the hand of a queen. Hamlet feels that his sense of reality is being eroded by the many falsehoods that surround him. He is thus led to wonder, as Werther does – is life worth living at all? The young Mahler felt similarly alienated from the society around him, not just because of differences of ethnic background, but because he believed that he perceived a bitter truth. Beneath the surface of the bourgeois world, Mahler believed that Nature was suffering, and that the human soul was sick.

Despair of this kind was not new. Such a dark perspective, stripping the human condition bare, could have been written by the pessimistic philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer, who was one of the most influential thinkers of the age. There was also an established tradition of German romantic artists dwelling on such gloomy subjects. More than half a century before Mahler’s first song-cycle, Schubert’s Winterreise had followed a by now familiar course. Rejected by his beloved, the protagonist embarks on a winter journey through a colourless, ice-bound landscape. If he is not worthy of love, and if love can never be freely expressed, then his existence becomes a living death. But this was also not the first time that Schubert had explored a destructive infatuation. In a pre-echo of Mahler’s Wayfarer songs, the jilted wanderer of Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin drowns in a fast-flowing stream. Released from his suffering, Mother Earth comforts the lost soul with a lullaby. Death is here a return to the womb, and a chance for the broken-hearted lover to be reborn.

The catalogue of suicidal romantics, in fiction and real life, is long. Robert Schumann, another poet of the broken heart, threw himself into the Rhine in a failed suicide attempt while, in Mahler’s student circle, it was Hans Rott, a composer whom Mahler admired, who ended up in an asylum ranting against Brahms. Rott died there in 1884, aged just 25, his talent unrealised. The inherent self-destructiveness of the romantic outlook took its toll, right up to the end of the Second World War, and we should therefore read Goethe’s story of Werther not as an endorsement of the romantic worldview, but as a critique of its absurdities and excesses. Werther is portrayed as precious, self-obsessed and whimsical, someone lacking discipline over his emotions. He wants to appear glamorous and unconventional, because that attracts admirers. Even his suicide can be viewed as just one final coup de théâtre. He shoots himself in the heart, leaving nobody in any doubt why he has killed himself. Charlotte, his beloved, is herself also not beyond criticism. She cannot marry him because propriety will not allow it, but she indulges Werther, time after time, as if he were a helpless child.

II. The world tree, shape-shifting and the afterlife

In Goethe’s novella, Werther’s suicide note requests that he should be buried next to two linden trees on the edge of the local churchyard. This should not surprise us, because the linden or lime tree holds a special place in German folklore. It signifies a crossing-point between the temporal and the eternal, and is thus a symbol of life and death, of fertility and immortality. The linden tree heals emotional wounds and remove resentments, so that there is an association with restorative justice and fairness. In the shade of the linden tree, love is made forever true, because the pain of separation in the afterlife is no longer endured. These symbolic functions explain why Werther request that he should be buried by the linden tree. It will correct the imbalances of his life, drawing him towards peace and harmony, while his love for Charlotte will be made perfect beyond the grave.

The blossoms of the linden tree are also noted for their intense and sensual aroma, which is not unlike the honeysuckle. The intoxicating scent stimulates erotic arousal and encourages lovemaking, reinforcing the tree’s connection not only with fertility, love and marriage, but also with states of altered perception and direct access to the unconscious realm. The linden tree is at one level simply the Tree of Life; a symbol of the great unity of all living things; a numinous manifestation of a deep truth which we can never directly know.

Goethe’s interest in the linden tree was not restricted to its role as a poetic and mythic symbol. He was a scientist, who was always curious to verify his theories about Nature. He believed that the behaviour of organic matter and the meaning of existence were somehow interconnected. In April 1820, Goethe exchanged letters with Carl Gustav Carus[iii], the famous anatomical illustrator and theorist of landscape painting. Carus recounted to the great man that he knew of a linden tree that located close to four coffins, which had recently been uprooted. The tree was found to have preserved the shape of the corpses, surrounding them with a fine lattice of roots which had also absorbed the mouldering flesh. Goethe asked for a sample of the roots to be sent to him, and Carus obliged. From this evidence Goethe concluded that the linden tree was not only a symbolic gateway to the eternal, but that it was enacting the symbol in a literal way by recycling the human body into the landscape.

In this light, we should not be perplexed to discover that, at the end of the Songs of a Wayfarer, the protagonist lies down to sleep at the foot of a linden tree. We are unsure whether he dies there, but the wounded lover undoubtedly achieves a deep spiritual union with Nature. We can be sure that Mahler was aware of the tree’s symbolical significance. He writes again in 1879 to his former schoolfriend, Josef Steiner:

But in the evening when I go out to the heath and climb a linden tree that stands there all lonely, and when from the topmost branches of this friend of mine I see far out into the world: before my eyes the Danube winds her ancient way, her waves flickering with the glow of the setting sun; from the village behind me the chime of the eventide bells is wafted to me on a kindly breeze, and the branches sway in the wind, rocking me into a slumber like the daughters of the elfin king, and the leaves and blossoms of my favourite tree tenderly caress my cheeks. – Stillness everywhere! Most holy stillness! Only from afar comes the melancholy croaking of the frog that sits all mournfully among the reeds.

We are firstly struck by Mahler’s instinct for melodrama. He acts, feels and expresses himself in the inflated rhetoric of a character in a novella by Eichendorff or Goethe. Up in the linden tree, he looks down upon the world. The tree’s physical presence heightens his senses, and there is a mood of religious awe. The sounds of Nature combine with the sounds of church bells to connect the human and natural worlds. It is as if they form parts of a single tableau of meaning. The Danube is his river of destiny, heading towards Vienna, while the linden tree and church bells seem to be parts of a ritual which connects him to the divine presence. Mahler is like a spiritual radar system picking up countless hints and signals from beyond the surface of appearances. Yet the price of this intense way of being is alienation from ordinary life and the experiences of most other people, who are not aware of the numinosity that surrounds them.

The origins of this worldview may be found in the philosophical writings of Friedrich Schelling (1775-1854)[iv]. He concluded that only art could truly express mankind’s profound connection to Nature by articulating the reality of the anima mundi or world soul. Schelling had been part of Goethe’s inner circle and was a major influence on Carus’ theories of landscape painting. Not surprisingly, Carus was a chief advocate of the landscape painter, Kaspar David Friedrich, whose work became emblematic of German Romantic feeling and which draws out the numinosity of Nature. It was a way of relating to Nature which appealed greatly to Goethe. Not long before his death in 1832, the old man completed Part II of his poetic masterpiece, Faust. The text of the final scene, which depicts Faust’s redemption, was famously set by Mahler in the second part of his 8th Symphony. When Faust dies, he falls into a rocky abyss, before various mystical figures carry him aloft to receive the healing embrace of the Mater Gloriosa or Queen of Heaven. Nature, Eros and divine spirit are revealed to be aspects of one unified reality.

The more sceptical minds of the day felt that such metaphysical speculations were just magical thinking. The idea of trees absorbing human souls was truly the stuff of fairy tales and deserving of parody. The famous illustrator Moritz von Schwind[v] made an engraving of trees taking on human form in a manner which anticipated the mythical fantasies of J.R.R. Tolkein. But the satire reinforces the point that, in Mahler’s worldview, matter is always animated by spirit, including the rocks and seas. The Earth is conceived as a single shape-shifting organism to which humanity unequivocally belongs.

This interfusion of subject and object, spirit and matter, conscious and unconscious mind, brings us to another influential figure in Mahler’s formative years; Gustav Theodor Fechner (1801-87). Fechner was allied to the more holistic strand of German philosophy represented by Schelling. He differentiated the joyous Day-View (Tagesansicht), which was the path to transcendent knowledge, from the materialistic Night-View (Nachtansicht)[vi], which he believed led only to separation and atheism. Fechner liked to bridge divides, venturing into metaphysical subjects which most scientists would have considered beyond their reach.

Some of Fechner’s thoughts in these areas were expressed in his Little Book of Life after Death which first appeared in 1836. In this text, Fechner elaborates what happens when we die, namely that the boundary between subject and object completely dissolves. We become then, he claimed, only what we feel, which flows unbounded directly back into the creative processes of the material world. In Fechner’s opinion, the physical and spiritual were two manifestations of the same reality. Thus, a change in one dimension leads to a corresponding change in the other. We know that Mahler read and admired Fechner’s texts, and he would have discussed them with his friend, Siegfried Lipiner, who had been Fechner’s pupil.

Reading that the dead were in a place unhindered by the inertia and separations of earthly existence would have been a great comfort to Mahler after the death of his brother, Ernst. He would have needed solace to cope with the shock, grief and guilt which would have accompanied such a bereavement. Mahler would lose another sibling in 1895, when his brother Otto, also a gifted composer, some thirteen years younger than Gustav, shot himself with a revolver.

Here was another disappointed Werther-figure, who could not deal with life’s challenges. Gustav would have had every sympathy with Otto’s predicament, for he was similarly sensitive and unstable. He too felt emotions to excess, but Gustav had turned his personal experiences into creative material, imbuing his interior narrative with coherence and meaning. Yet, Mahler, the artist still needed the sorrows of the wounded boy to provide the drama and intensity of his vision, even if the wounded boy felt horror faced with such ruthless demands.

III. Mahler the Titan

We have learned a lot about Mahler, the suffering sensitive young man. But Mahler was a multi-faceted personality and part of him was also a Titan. In Greek mythology, the Titans were the original primitive gods overthrown by the Olympians. They were cast into the underworld, where humanity was fashioned from their burning corpses. The story was intended to explain the origin of the excessive and transgressive aspects of human nature, in contradistinction to the gentleness of the soul. In the romantic period, the Titan came to represent a willingness to challenge authority and orthodoxy, and Mahler’s Titanic side can be identified with these characteristics. If the Mahlerian soul recoiled in horror at the injustice and misery of the world, Mahler the Titan wanted to change things by the force of his will.

Young Gustav arrived in Vienna from the Bohemian provinces on 10 September 1875 to begin a new life as a musician. His studies would last three years, bringing him into contact with other leading talents of his generation, including the composers Hugo Wolf and Hans Rott. Despite poor living conditions, Mahler worked hard, taking every opportunity to educate himself more broadly. In October 1877, Mahler signed up for lecture courses in general arts and philosophy at the University of Vienna. He also became a member of a lecture club, the Leseverein des Deutschen Studenten, which introduced him to the latest thinking about the pessimistic philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) and the visionary iconoclast, Friederich Nietzsche (1844-1900), then still very much a living, controversial figure. One of the regular speakers at the Leseverein was a young firebrand playwright called Siegfried Lipiner, who would become a close friend of the Gustav.

By the time Mahler’s Conservatory courses came to an end in June 1878, he was ready to embark on a conducting career that would take him to several major opera houses across Central Europe. It was his journeyman period; a chance to learn about the realities of a professional life in music, which meant discovering that standards were often mediocre, money in short supply and employers less than sympathetic. Mahler stayed in touch with his Vienna circle although, around this time, the government authorities closed the Leseverein down, claiming it to be seditious and a threat to public order. However, many of the former attenders continued to meet unofficially under the banner of the ‘Pernerstorfer’ group, which included committed socialists and radical thinkers such as Lipiner, the archaeologist Fritz Löhr and the future socialist leader, Viktor Adler. At the centre of their social and political debates were the writings of Schopenhauer, Nietzsche and Wagner. The Pernerstorfer group were passionate aesthetes, who believed that societies should be bound together by the visionary feelings expressed in romantic art, rather than by rational forms of governance. The leading figure, from whom the group took its name, was Engelbert Pernerstorfer (1850-1918), who was both a socialist and a pan-German nationalist, inspired by the example of Richard Wagner. Wagner’s music dramas provided a reinvigorated mythology intended to unite German culture as never before. It is fair to say that the group were authoritarian in cultural matters, believing in the power of genius. Mahler, who played the piano at some of their meetings, would have had much sympathy with this view and, as a conductor, he would have felt entitled to demand absolute obedience and self-sacrifice from his musicians in pursuit of his goals, which often included the performance of Wagner’s music.

Richard Wagner

The Pernerstorfer group was, like Wagner, strongly influenced by Schopenhauer’s metaphysics which encouraged compassion for the struggles of all humanity, while promoting art as a primary means to transcend the indiscriminate Will which creates the suffering of our existence. The artist and philosopher were in Schopenhauer’s eyes superior beings; sources of wisdom and authority, while music, above all the arts, offered a direct knowledge of the Will because it addressed feeling, not the intellect. In Schopenhauer’s philosophy, composers were akin to prophets and saints, able to transform and elevate human suffering. Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophical ideas also dominated the group. His vision of transcendent joy and dynamic self-actualisation invited men of vision to embrace life’s many contradictions. His high-minded iconoclasm offered to liberate artists like Mahler from the outmoded dogmas and social norms perpetuated by institutions such as the Church and imperial authorities. Mahler would later follow a more conservative path, converting to Catholicism and serving the Imperial Court. We should never underestimate that Mahler the Titan was willing to sacrifice Mahler the idealist and Mahler the unhappy child, when it suited him.

However, no amount of exuberance can conceal that Nietzsche’s outlook on the human condition was essentially tragic. To live a life to its fullest potential was no soft option. Nietzsche knew from personal experience that an individual who dared to rise above the masses risked ridicule and isolation. But one figure had apparently succeeded in conquering all. In this regard, the life and work of Richard Wagner were a towering example to the ‘Pernerstorfer’ group. The mature Wagner stood for Schopenhauerian ascetism, the primacy of music as an art-form and the cathartic power of tragedy to help the human individual carry the burden of his heroic existence. Wagner was also considered a cultural leader among pan-German nationalists, while his vicious anti-Semitism was something which Mahler was compelled to overlook. While Parsifal, Wagner’s final vision of German culture reborn, was not due to be performed until 1882, the mighty Ring Cycle, first performed in 1876, had left its mark on intellectual circles. It depicted a world corrupted by greed and materialism, heading towards calamity; a world of corrupt gods and wilful blindness. The work’s apocalyptic denouement would later provide a model for the conclusion of Mahler’s Das klagende Lied, which diagnosed a similar societal malaise.

We know that Mahler was a fanatical follower of Wagner in his youth and remained a devotee of his music throughout his life. In younger days, Mahler was eager to prove himself a cultural radical in the same mould as Wagner. He was willing to support the pan-German vision of the Pernerstorfer group, because he had found friendship there and an outlet for his youthful idealism. However, in the late 1870s, nothing indicated that Mahler would follow in Wagner’s footsteps as a composer of large-scale works exploring metaphysical subjects. There were just a few modest chamber-pieces and a handful of songs. Only after his graduation from the Conservatory in 1878 did Mahler begin to reveal his creative originality. It can be argued that it was his contact with the intellectual hothouse of the Pernerstorfer circle which made the crucial difference. They helped him hone the distinctive philosophical preoccupations of his first four symphonies, as well as the many songs from which they germinated.

IV. Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen – Songs of a Wayfarer

Now that we know something of Mahler’s development during his student years, we can approach his first song-cycle, the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, with a more sophisticated understanding. In 1883, Mahler was in his early-twenties gathering experience as a conductor in the opera houses of Central Europe. That year he arrived in Kassel, Northern Germany, where he had become an assistant to the aging Kapellmeister, Wilhelm Treiber. Kassel is famous as one of the major centres of the German fairy-tale cult. It was where the Grimm brothers published two volumes of their famous legends. However, despite its literary reputation, the city’s opera company was rather mediocre, and so Mahler was eager to raise standards there, applying himself with his customary fanatical energy.

But his ambition soon gained him a reputation as an upstart who irritated both Treiber and his aristocratic employers. Mahler made matters worse by falling in love with Johanna Richter; an attractive, blue-eyed soprano lodging in Treiber’s house. The affair caused Mahler’s relationship with his superior to deteriorate beyond rescue, and the young apprentice conductor soon realised he no longer had a future in Kassel. He began searching for a new job, throwing his relationship with Johanna into crisis. On New Year’s Eve 1884, the couple, knowing their fate was sealed, parted in tears. Mahler walked into the dark streets at midnight, writing later to his friend Fritz Löhr from the Pernerstorfer group with a tortured account of his feelings:

When I came out of the door, the bells were ringing, and the solemn chorale rang out from the tower. Ah dear Fritz, it was just as if the great stage-manager had wanted to make it all artistically perfect. I wept all through the night in my dreams.

It is typical of Mahler already to sense the creative potential of his broken heart. But the theatrical scene he describes was perhaps more colourful than the mundane reality. Things turned out somewhat less dramatically than suggested by his letter. The doomed couple continued to work together for a further six months before Mahler finally left Kassel to take up a new post in Prague. Creatively, the high emotion of the relationship had already born fruit. During the previous year, Mahler had written six poems for Johanna, expressing his elation and sadness. The poems mimicked the vernacular style associated with Kassel, and in 1885, Mahler set four of them for voice and piano. He called the work, Geschichte von einem fahrenden Gesellen which later became Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen or Songs of a Wayfarer. To be more precise, we should translate the title as: “Tales”, or in the later version, ‘Songs of a wayfaring journeyman”. Mahler’s choice of the term Gesellen or journeyman is important, because it carries a very specific meaning in the iconography of German Romanticism. It suggests someone whose status is between an apprentice and a master; a man in transition, who is not yet fully free of authority. This makes an obvious autobiographical connection with the young Mahler, who was still learning his trade.

There is little question that Mahler’s life experiences contributed directly to his musical projects, and his Songs of a Wayfarer were no exception. Yet these lyrical miniatures did not simply express Mahler’s personal feelings about Johanna, for he adapted them to make more universal statements about the human condition. We know this to be true because, based on the facts of the story, we would expect this song-cycle to concern a hero forced to abandon his beloved but, in the first song, Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht, it is she who has abandoned him. The day she marries, the wayfarer predicts, he will go to his room and weep. The victim here is the male protagonist, and Mahler expresses the wayfarer’s misery and alienation through music of two contrasting speeds. The short piano introduction evokes a wedding dance, but when the voice enters, imitating the dance, the tempo is lethargic, and the atmosphere filled with pathos. The wayfarer cannot respond positively to the nuptial celebrations, for they symbolise the deceptive world of appearances which deny him happiness.

We should focus our attention for a while on that little introductory figure. It is a simple turn-like motif – down two notes and then back up again – something you might whistle to yourself.[vii] But we will discover that this is an important feature of the cycle, which constantly reminds us of the work’s opening and the wayfarer’s predicament, which is best summarised by the question ‘to be or not to be?’

The middle section of this first song is more fluently lyrical. We meet for the first time a third character in this mini-drama. Nature appears in the form of a bird. Its singing momentarily delights the wayfarer, but the wedding dance-motif can still be heard, even if it has been transformed into ecstatic birdsong. This an expression of Nature’s joy, as was also intended by the idea of a wedding dance. But the motive serves to remind us that wounded feeling still poisons the air, as the wayfarer recalls his separation from his beloved and from the social world. In the song’s final section, the opening phrases return with added intensity, as dusk descends and the wayfarer slumps into depression.

Having left the wayfarer in a state of deep melancholy and despair, the second song of the cycle, begins at dawn on another day. The gloom has lifted. The D major of Ging heut’ morgen übers Feld, presents the wayfarer in high spirits. A bird sings to him, echoing the chirping of the first song. All seems well, but confidence soon ebbs away. The wayfarer cannot forget his pain, and we hear again the wedding dance-motive again amidst the birdsong.

Hereafter, the music starts to slow down, as once again the memory of love betrayed infiltrates the wayfarer’s thoughts. The bird too falls silent. The final bars, in the remote key of F-sharp major, are full of bliss and heartache, as the wayfarer asks – “now surely my happiness begins? “…but in resignation he answers his own question, “No! No! What I love can never bloom for me!”

This moment, when the transience of all beauty and human joy is so poignantly expressed, was remarkably anticipated by the philosopher and scientist, G.T. Fechner in his Little Book of Life after Death. He writes:

But death is only a second birth into a freer existence, in which the spirit breaks through its slender covering… Then, all that reaches our present senses as mere exterior…will penetrate us fully and will be possessed by us in all its depth of reality. The spirit will no longer wander over mountain and field, surrounded by the delights of spring, only to mourn that it all seems exterior to him; but, transcending earthly limitations, he will feel new strength and joy in growing.

The third song, Ich hab’ ein glühend Messer, unleashes terror and violence. It is night again, but there can be no sleep, for the wayfarer has a metaphorical red-hot blade in his breast. The music employs fragments from the earlier songs, but these are made restless by displaced the accents and by the use of the minor key. The effect is disorientating. Visceral emotions are expressed by shrieks and sighs. Thereafter emerges an anxious stillness which heralds a vision. But, instead of Nature’s beauty, the wayfarer is haunted by the two blue eyes of his lost love. The wayfarer has always wanted more than a loving companion, for his beloved has represented his very soul. Like Werther, seeking perfect love has led him only to inevitable failure and suicidal despair.

The red-hot knife is the symbol of that love betrayed, inflicting a wound that cannot be healed. This may be a reference to the plot of Wagner’s Parsifal, in which death is the only means to release Amfortas’ from his suffering. He is a king with a wound that will not heal, and which symbolises his separation from Nature. At the climax of Mahler’s song, the wayfarer too wishes he was dead; his eyes shut on the bier. The music’s intensity shatters everything, giving full vent to the wayfarer’s agony. The suffering individual now seems to speak for the whole Universe, as his pain resonates throughout the cosmos.

Some level of emotional containment is restored in the final song, Die zwei blauen Augen – The Two Blue Eyes. It opens with a funeral march; its slow tread interrupted by hesitant pauses. Funeral marches often occur in Mahler’s music. They represent resignation to what must be; a slow procession through earthly woes, something akin to Schubert’s Winter Journey. The wayfarer now regrets being drawn into life by the two blue eyes which had promised him the joys of love. They have been the cause of much anguish. The march reaches the key of C, over a bell-like bass. As the harmony vacillates obsessively between major and minor; the voice tracing a twisting, sighing plaint. It is as if the Wayfarer cannot decide whether to say yes or no to life, shifting between joy and sadness, hope and resignation.

Disillusioned with the ordinary world, the wayfarer goes out to the moor where he sinks into unconsciousness or even death. In the manner of Schubert, a lullaby provides the consoling presence of Mother Nature. In this episode, the D minor of the cycle’s opening finds resolution in the related key of F major. But listen carefully, and we can still hear that wedding dance motive woven serenely into the texture, as the wayfarer falls asleep under a linden tree. We know that this tree has not been randomly chosen. It symbolises a gateway to the eternal and the healing of wounds. It offers a once doomed love the chance to become for ever true.

All boundaries dissolve, as the music merges “love and suffering, world and dream”. Yet, in the very last bars, the funereal tread reappears in the minor key; a doom-laden question-mark, reminding us that grief and separation await the wayfarer if he chooses to return to the waking world.

V. Relationship with the First Symphony

I want to conclude with some brief closing remarks about the song-cycle’s relationship with the First Symphony. Mahler clearly intended there to be thematic and narrative links between the Wayfarer Songs and his First Symphony, but the final outcomes of these works could not be more different. The songs were of course only one source among many which spurred Mahler’s imagination as he developed his highly original symphonic project. Another influence was Jean Paul’s extravagant novel Titan, which had at one stage provided the symphony with a title and a programme. The novel, published in four volumes between 1800-1803, is notable for its inventive structure and flights of fancy which anticipate Mahler’s own phantasmagoria. Its characters display the kind of extreme impulses which we might associate with the young Mahler. The Titan of the book’s title is a man called Roquairol who possesses no moral boundaries. At the novel’s climax, his self-indulgence turns to self-pity as, in the manner of young Werther, he deliberately shoots himself while acting on stage in a play. While this appears to be a drastic expression of remorse for his previous shocking behaviour, it also shows that Roquairol cannot face those he has wronged, nor bear the shame of his moral failure. His nihilism leads him to live and die with thoughtless egoism, showing us that the cruel Titan and the wounded child are able to exist as opposites within the same individual.

Mahler’s hero in the First Symphony is a Titan for good and ill; a transgressor at odds with society. His identification with such a figure positioned him as a revolutionary artist who possesses the boldness to bring forth his message. Yet this leaves little space for the damaged inner child, who shrinks from pain and confrontation. The symphony’s finale struggles towards an overwhelming heroic triumph, sweeping aside any hint of gloomy sentiment or the gentle transcendence found in the song cycle. Mahler’s comments to his companion Natalie Bauer-Lechner, made albeit a decade after the Wayfarer songs’ composition, indicate that he felt they were too tragic in character:

Mahler himself said that anyone hearing them [the songs] would be totally shattered ‘I’m not happy about it, for the aim of art, as I see it, must always be the ultimate liberation from and transcendence of sorrow. Admittedly this aim is achieved in my First but, in fact, the victory is won only with the death of my struggling Titan. Every time he raises his head above the surging waves of life…he is struck down again by blows of fate.[viii]

Mahler appears to chide himself here for his adolescent despair in the Wayfarer songs, and we might be persuaded to read the symphony as a repudiation of their tragic ending. But what brings about this transformation? Nietzsche may provide the answer. If the Songs of a Wayfarer are allied with Schopenhauerian pessimism and denying the will to live, the First Symphony seeks to transcend the human tragedy and reaffirm life’s creative possibilities. In The Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche states that it is the absence of the joyous spirit of Dionysus which drains our experience of depth and meaning, sapping our willingness to embrace life in its totality. Apollonian beauty on its own is too misleading and superficial, the veneer of the bourgeois world. By contrast, music that is born from the Dionysian spirit of tragedy promotes vitality, transforming our sadness into joyful wisdom, because it breaks down the illusion of our separateness. Nietzsche writes:

In the views of things here given we already have all the elements of a profound and pessimistic contemplation of the world, and along with these we have the mystery doctrine of tragedy: the fundamental knowledge of the oneness of all existing things, the consideration of individuation as the primal cause of evil, and art as the joyous hope that the spell of individuation may be broken, as the augury of a restored oneness.[ix]

The end of the Songs of a Wayfarer is a first step towards restoring oneness, and the symphony turns this struggle for transcendence from a personal confession into an epic drama. In its stormy finale, battle ensues between the regressive pull of the wounded child and the Dionysian energies which draw the hero back into life. Eventually, the unruly Titan is reborn as an authentic hero; one who is strong enough to say ‘yes’ to his existence. But, since this is Mahler, the hero overplays his hand. The Songs of a Wayfarer hint that the struggle is likely to begin all over again, because the Titan and the wounded boy are not so easily reconciled.

©Peter Davison

Colorado Mahlerfest

Boulder, Colorado

18 May 2019

All rights reserved. No portion of this article may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic of mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information or retrieval system without permission in writing from the author.

Please contact the author via peterdavison@helios-arts.net

Appendix 1

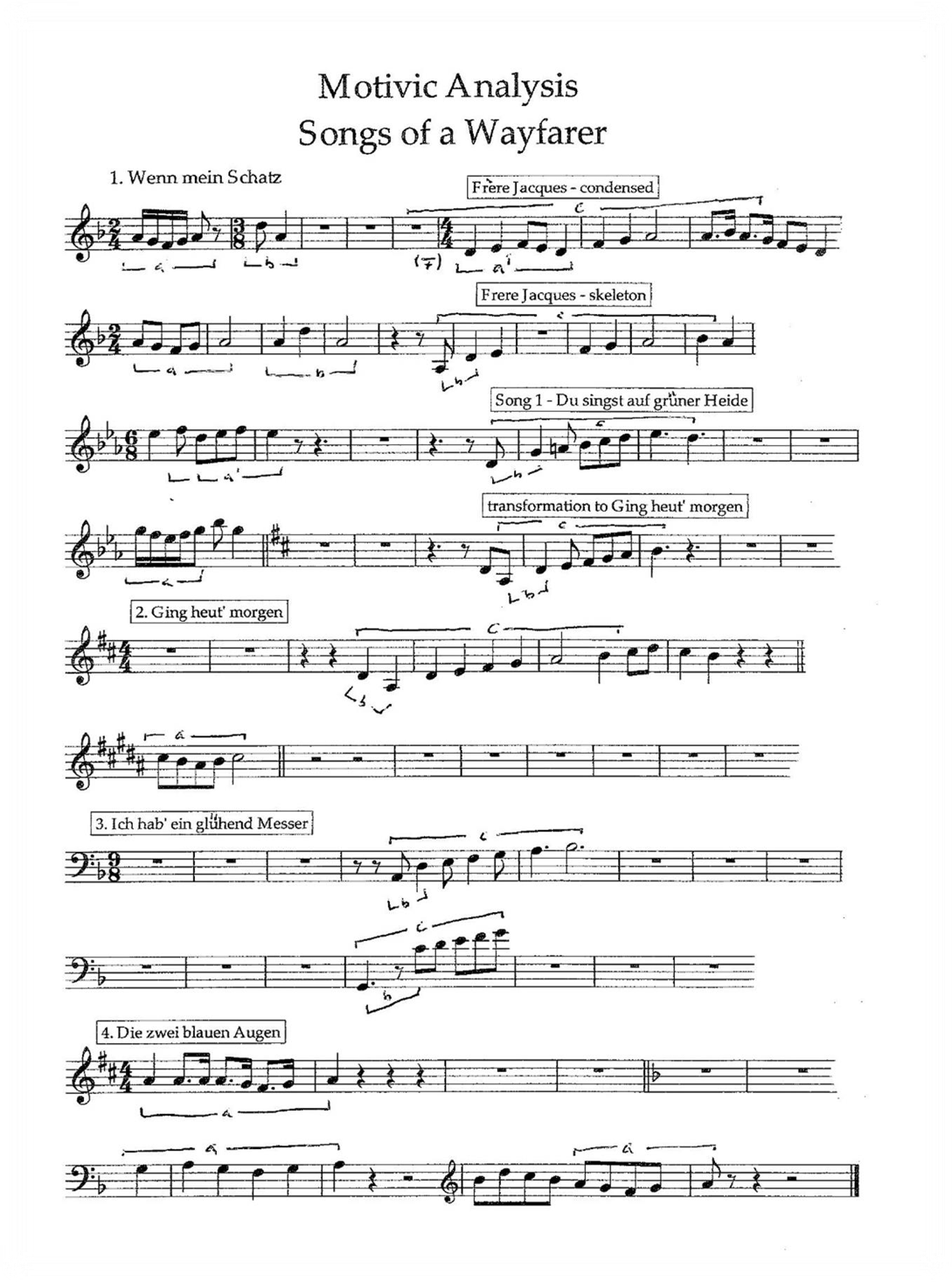

Motivic connections and thematic links with the First Symphony

The Songs of a Wayfarer are well-known as the source for much of the thematic material of Mahler’s First Symphony. There can be little doubt that Mahler intended these connections to assist in creating the symphony’s philosophical and psychological narrative. The sheer abundance and diversity of the source material upon which Mahler drew during the composition of the First Symphony risked incoherence, and this may explain why he subsequently suppressed so much of the work’s programmatic background following the work’s first performance in Budapest in 1889.

The musical links between the song cycle and symphony are tonal, thematic and motivic. The opening song is in D minor; the key of the symphony’s slow movement, and one can discern some family resemblance in the motives of this first song (Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht) and the Frère Jacques theme of the symphony’s funeral march (See motivic analysis below). The middle section of that movement is borrowed directly from the linden tree music of the cycle’s last song, which also provides the dotted countermelody of the funeral march itself. In the symphony, there are thematic and motivic relationships with material drawn from all the songs. Most obviously, the second song (Ging heut’ morgen) provides the main theme of the symphony’s first movement which is also in the same key of D major. The theme generates the birdsong motives heard in the symphony’s slow introduction. The pervasive interval of the fourth (either rising or falling) dominates both the song cycle and the symphony. The falling fourth which serves to imitate the call of the cuckoo in the First Symphony can be heard in the second measure of the first song and the second measure of the second song. It becomes a rising fourth in the third song and again in the F major section of final song. The fourth can also be heard as a bell-like bass from measure 17 of this song, which may reference Mahler’s letter to Fritz Löhr about the drama which occurred at midnight on New Year’s Eve in 1884.

Less clearly audible are the motivic connections which bind the four songs together. The bassline of the first song (measures 14-18) anticipates the rising fourth of the second song and its thematic elaboration. In the middle section of the first song, we hear various transformations of the turn-motif which opens the cycle, while the melody which accompanies the words ‘du singst auf grüner Heide’ in the middle section of the first song, recurs in the third song (measures 7-8) with a variant in measure 48 which also reappears in the final song.

Perhaps most striking is the consistent recurrence of the turn motive which opens the cycle. It is found in the second song as the melody accompanying the bird’s greeting, ‘Guten Tag’ in B major, and again in measures 3-4 of the final song. It is also discretely placed as an inner voice (although prominently marked in the piano score) in measures 42-44 of the same song. This motive seems to represent the natural joy of nature expressed by the bird but, at the start of the cycle, it evokes the joyful exuberance of the wedding dance from which the wayfarer feels excluded. The final appearance of the motive in the serene F major section of Die zwie blauen Augen might suggest that the Wayfarer is at last reconciled to Nature and the joy which lie beyond ego and the suffering of mortal existence, as the wayfarer sinks into unconsciousness.

Notes

[i] From the closing scene of Mahler’s first major published work that included orchestra, Das klagende Lied – The Song of Lamentation (1878-80)

[ii] Ernst died of the same endocarditis infection which would kill Gustav in 1911.

[iii] Carl Gustav Carus (1789-1869) graduated in medicine and philosophy. A renowned anatomist and anatomical illustrator, he taught himself oil painting by working under Caspar David Friedrich, eventually developing his own theory of landscape-painting in his Neun Briefe über Landschaftsmalerei (1819–1831).

[iv] See Schelling’s three key works that define his Naturphilosophie:

Ideen zu einer Philosophie der Natur als Einleitung in das Studium dieser Wissenschaft 1797 (Ideas for a Philosophy of Nature as Introduction to the Study of this Science)

Von der Weltseele 1798 (On the World Soul)

Erster Entwurf eines Systems der Naturphilosophie 1799 (First Plan of a System of the Philosophy of Nature).

[v] Moritz von Schwind (1804-71), an Austrian artist and illustrator, best known for his depictions of fairy tales and other ironically humorous images, including The Hunter’s Funeral Procession (1850), which inspired the third movement of Mahler’s First Symphony.

[vi] Gustav Theodor Fechner (1801-87), physicist and philosopher.

Das Büchlein vom Leben nach dem Tode (1836) (published in English as The Little Book of Life After Death (1904) with a forward by William James)

Die Tagesansicht gegenüber der Nachtansicht (1879) (translates as The Day View as opposed to the Night View)

[vii] See motivic analysis in Appendix One

[viii] Natalie Bauer-Lechner (1858-1921), Recollections of Gustav Mahler trans. Dika Newlin, ed. Peter Franklin, Faber & Faber 2013

[ix] Friederich Nietzsche (1844-1900), The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music (1872) trans. Shaun Whiteside, ed. Michel Tanner, Penguin Classics 1993