A few years ago, Julian Johnson’s excellent book “Mahler’s Voices” had been languishing on various bookshelves here in an embarrassingly half-read state.

Eventually, with a performance of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony on the horizon, I began skimming through relevant chapters. Almost immediately, I spied something a bit provocative (no pun intended) on the subject of Mahler and sex.

Nothing marks this difference more acutely than the absence of an erotic dimension in Mahler’s work. The preoccupation of Viennese modernism with a specifically sexual content (Klimt, Gerstl, Schiele, Kokoschka… Strauss, Zemlinsky, Schreker, Schönberg) is entirely bypassed by Mahler. Despite a lifelong engagement with the music of Wagner, and memorable performances of Tristan und Isolde, Mahler’s own music displays a studied avoidance of the topic that most immediately defined a modernist viewpoint. (Page 229)

Oskar Kokoschka – “Alma Mahler with Her Future Lover”

It’s funny how differently various perceptive listeners will hear the same piece of music. The rest of this paragraph from Johnson is a tour de force of insight, nuance, and complexity, but in these two sentences, I saw before me the possibility of a blog post with a blatantly titillating title in which I could mix a bit of juvenile humor with some more thoughtful insights in the complexities of Mahler’s musical world.

Sex is often depicted in the modernist works of Mahler’s near contemporaries and immediate successors as something dark and dangerous. It is frequently associated with decay and madness, and with isolation, rage, manipulation and estrangement. Sex in Berg, Schoenberg, and Richard Strauss is probably more likely to be associated with murder than with love. Wagner adds incest. In Mahler, with the notable exceptions of Das Lied von der Erde and the “Scherzo” of the Fifth Symphony, sex is a redemptive, healing, creative force, closely joined to the idea of transcendent love. Which vision of sexuality is more truly modern? The darker sexual images of most early 20th C. modernist art may make Mahler’s worldview seem sweetly old-fashioned, but they clearly bind sex with shame. Maybe there is something distinctly modern about Mahler’s un-embarrassed depiction of sex as something essential, even holy?

While I wouldn’t say that, as a rule, Mahler’s music gets quite as raunchy as the purple-est passages in the music of the Richard’s, Strauss and Wagner, I’m pretty confident in asserting there are some pretty good naughty bits in Mahler’s music. So, without further ado, I present for the record, the official, definitive, ultimate, Real Top Ten Sexiest Moments in the Music of Mahler.

What do you think? Are there passages in Mahler that get you seriously hot and bothered, or do you turn to Lulu and Salome for your fix of early 20th c. Austro-German sensuality?

10- “Die zwei blauen Augen” (My Baby’s Blue Eyes) from Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen

We hear a funeral march, then the voice of the poet, a young wayfarer, describing the beauty of his beloved’s two blue eyes. Is it a love-song or a lament? Is it about sex or death? Why not both? Mahler is singing a Bohemian blues, or is it a country/western lament? It’s a tear-in-your-beer tale of a pretty girl and a broken heart, no doubt, and when the clouds part and the poet lies back under the linden tree and remembers his beloved, it’s abundantly sad and sexy.

The two blue eyes of my darling –

they have sent me into the wide world.

I had to take my leave of this well-beloved place!

O blue eyes, why did you gaze on me?

Now I will have eternal sorrow and grief.

I went out into the quiet night well across the dark heath.

To me no one bade farewell. Farewell!

My companions are love and sorrow!

On the road there stands a linden tree,

and there for the first time I found rest in sleep!

Under the linden tree

that snowed its blossoms onto me –

I did not know how life went on,

and all was well again!

All! All, love and sorrow

and world and dream!

9- Trio in “Movement II – Kraftig Bewegt” from Symphony No. 1

An interesting point of comparison with the waltz music in the Fifth Symphony (see no. 7 below)- these two passages share many of the same dance rhythms, and both are plenty alluring in their way, but this episode is a more innocent kind of sexy. This passage is more a sort of “sweet fraulein from the village flirting in a dirndl in a kind of semi-innocent way” sexy, where the parallel passage in the Fifth is full of fin de siècle decadence and danger. But a dirndl can still be sexy.

8- “Adagietto” from Symphony No. 5

A love-letter to his wife, or meditation on mortality and loss? Is it about sex or is it about death? Commentators have debated this question for over a hundred years. Of course, the answer is obvious- for the generation of composers after Richard Wagner, you can’t represent sex in a piece without at least a bit of death in it. At the very least, a Romantic outpouring of love needs a good dose of denial and disappointment. In Mahler’s most popular movement, episodes of tenderness alternate with explosions of angst. Any conductor who gives you only sex or only death in this one is not treating you, or the music, right.

7- “Scherzo” from Symphony No. 5

Mahler’s “damnable” Scherzo was apparently inspired in part by Goethe’s poem “An Schwager Kronos.” You can learn more here, or check out Donald Mitchell’s essay on the Fifth (not an easy read). Throughout the movement are several versions of a slow waltz that’s as sleazy as a Viennese brothel. Goethe’s words surely fired Mahler’s imagination:

A shadowy doorway beckons you aside

Across the threshold of the girl’s house,

And her eyes promise refreshment.

Take comfort! For me too, lass, that sparkling draught

That fresh and healthy look.

6- “Nachtmusik No. 2” from Symphony No. 7

You want sexy? He didn’t call it “Andante amoroso” for nothing This astounding movement starts with a rapturous “oh baby, you are looking hot tonight” slide in the solo violin, then piles on the mandolin and guitar.

5- “Von der Schönheit” from Das Lied von der Erde

Well, the title “Of Beauty” offers quite a hint. Then there’s the bit about the young maiden and the horse, which Freud would have loved. But it’s the meltingly beautiful coda that really shows Mahler’s music at its sexiest.

O see the handsome young men galloping

there along the shore on their lively horses,

glittering like sunbeams;

already among the branches of the green willows,

the fresh-faced young men are approaching!

The trotting horse of one whinnies merrily

and shies and canters away;

over flowers and grass, hooves are flying,

trampling up a storm of fallen blossoms.

Ah, how wildly its mane flutters,

how hotly its nostrils flare!

The golden sun weaves among the figures,

mirroring them in the shiny water.

And the fairest of the young women sends

a long, yearning gaze after him.

Her proud appearance is only a pretense.

In the flash of her large eyes,

in the darkness of her ardent glance,

the agitation of her heart leaps after him, lamenting.

4- Duo “O Schmerz! Du Alldurchdringer!” from Symphony No. 2

Nothing particularly sexy about the text, or the context, but there is something very sensual about Mahler’s writing for the two women’s voices in this brief episode from just before the end of the symphony. The sound of the two singers’ lines overlapping and dovetailing is really something- especially if you’re lucky enough to be standing between them.

3- Trio “Die du großen Sünderinnen” from Symphony No. 8 (Part II)

Again, when Mahler busts out the mandolin- you know the music is going to end up pretty sexy sooner or later. Listeners with a slightly juvenile perspective might find themselves tittering a bit when Mater Glorioso sings “Komm, komm,” but there’s something irresistibly sexy about about the effect Mahler gets from three women’s voices overlapping as they spin out “you who do not avert your gaze from women who sin.” This passage in Mahler’s most gargantuan work has been compared with the “Sirens” scene from the Cohen’s “Oh Brother, Where Art Thou?” Maybe that’s wrong, maybe that’s right. Who am I to say?

You who do not avert your gaze

From women who have sinned

Raise into eternity

The victory gained by repentance,

Grant also this poor soul,

Who only once forgot,

Who did not know that she erred,

Your forgiveness!

Anyway, Mahler dedicated the Eighth to Alma, and the final lines of his Goethe setting are rich territory for anyone looking for juvenile double entendres:

Here finds fulfilment;

The ineffable

Here is accomplished;

The eternal feminine

brings us up.

2- “Ich atmet einen Lindenduft” from Rückert Lieder

The Rückert Lieder may be Mahler’s most consistently sexy piece. “Bliecke mir nicht in die Lieder” (“Don’t flirt with me when I’m songwritin’, baby”) is wonderfully flirtatious, and “Liebst um Schönheit” (“Don’t love me ‘cause I’m hot, love me cause I love you, baby”) wonderfully honest and open-hearted.

But there’s something about “Ich atmet einen Lindenduft” (“I smell a sexy scent in the air tonight, baby”) that is genuinely sensual. The ever-symbolic linden tree makes its second appearance on this list.

I breathed a gentle fragrance!

In the room stood

a sprig of linden, a gift from a dear hand.

How lovely was the fragrance of linden!

How lovely is the fragrance of linden!

That twig of linden you broke off so gently!

Softly I breathe in the fragrance of linden,

the gentle fragrance of love.

1- “Finale” from Symphony No. 10

Perhaps because it’s the last movement of his unfinished final symphony, or because it is of the most beautiful, personal, and profound things ever created by a human being, you might expect me to show a little of respect and not go bringing the whole “sex” thing into a discussion of this valedictory work. But that’s not how we roll at Vftp (A View from the Podium). Yes- I’m going there.

Mahler wrote this movement while trying to rebuild his fractured relationship with Alma- the beautiful passage in the Finale that begins with the famous flute solo (in Cooke’s realization, but also specified as for flute in Mahler’s sketch) is sexy in a very complicated, painful way. There is music with an almost unmatched, unmatchable depth of feeling: so much longing, ecstasy, and intensity.

And what could be more devastating than when this passionate reverie is shattered by the recurrence of the hammer blows which open the movement? Wagner may have written the composer’s guide to milking the exquisite pain of unbearable longing pitted against absolute denial in Tristan und Isolde, but Mahler already showed in the Fifth Symphony that mixing sex and pain in music worked for more than just the leather-undies crowd. The music which follows this passionate outpouring is some of the most agonized ever written, culminating in a climax of shattering desolation (around 1:14:30 onward).

But in the final pages, the voice of love and longing returns, sexier than ever. A farewell to life or a return to the loving arms of his beloved? Haven’t you been paying attention- with Mahler, it’s never “sex” or “death,” it’s always “sex and death.” On the final page of his final symphony, Mahler elevates longing, love, and desire to a place of pure transcendence. The final string glissando is about as obviously passionate, sexy, and ecstatic a gesture as you’re ever going to hear in music, and here he writes “ALMSCHI!”

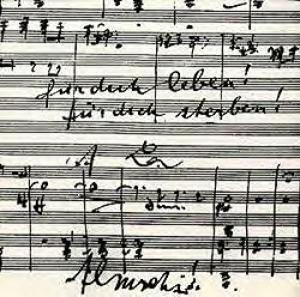

Mahler’s Score – Symphony No. 10

The last page of the manuscript of Mahler’s last work. “für dich leben! für dich sterben! Almschi” (To live for you! To die for you!–Almschi!)