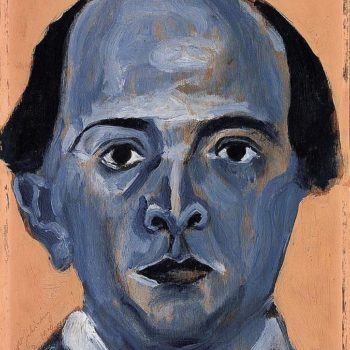

As a name, “The Society for Private Musical Performances” may not roll off the tongue, but it is surely easier to say for most of us than the German original “Verein für musikalische Privataufführungen”. The Society was founded by the composer Arnold Schoenberg with the intention of making carefully rehearsed and comprehensible performances of newly composed music available to genuinely interested members of the musical public. In the three years between February 1919 and 5 December 1921 (when the Verein had to cease its activities due to Austrian hyperinflation), the organisation gave 353 performances of 154 works in 117 concerts involving a total of 79 individuals and pre-existing ensembles. Devoted to fostering new discussion of emerging works, the Society did not welcome critics and audience members had to join the Society in order to attend.

As a name, “The Society for Private Musical Performances” may not roll off the tongue, but it is surely easier to say for most of us than the German original “Verein für musikalische Privataufführungen”. The Society was founded by the composer Arnold Schoenberg with the intention of making carefully rehearsed and comprehensible performances of newly composed music available to genuinely interested members of the musical public. In the three years between February 1919 and 5 December 1921 (when the Verein had to cease its activities due to Austrian hyperinflation), the organisation gave 353 performances of 154 works in 117 concerts involving a total of 79 individuals and pre-existing ensembles. Devoted to fostering new discussion of emerging works, the Society did not welcome critics and audience members had to join the Society in order to attend.

Works performed in the Society’s concerts reflected a huge range of the best of late 19th and early 20th Century works, but nothing by Schoenberg himself. Orchestral works were played in arrangements for small ensembles like the one you will hear tonight. Schoenberg himself made many of these arrangements, including the whimsical arrangement of the Strauss Emperor Waltz which opens our concert tonight, and he oversaw the work of other composers and arrangers including Erwin Stein, who arranged the Fourth Symphony of Mahler for a Society concert in 1921. There was no standard instrumentation for these concerts, but most of the arrangements that have come down to us from the Society are for some combination of solo strings, a few solo winds, piano and harmonium. This sort of salon orchestra was often augmented by the liberal use of percussion, which can greatly enhance the range of color. Schoenberg made his humorous and eccentric arrangement of Strauss’s greatest waltz for a fundraising concert in support of the Society in 1921 which also featured arrangements of Strauss waltzes by Schoenberg’s leading pupils, Anton Webern, who also played cello, and Alban Berg, who played harmonium. Schoenberg played first violin on the concert and served as the master of ceremonies for the event. It may surprise listeners to know that he earned special praise from the critics for his witty stage presence.

For much of the 20th Century, the arrangements of the Society were largely forgotten. In an affluent age, there seemed to be little need for arrangements of Mahler symphonies and songs for 10-15 players. However, in the last twenty years or so, these arrangements have seen a real resurgence, and have become recognised as being artistically interesting in their own right. From a listener’s point of view, they offer a more intimate view of the music, one that perhaps allows the creativity and artistry of the individual performances to shine through. I’ve conducted and recorded a lot of the arrangements from the Society and have become thoroughly seduced by their unique sound world. I hope those of you new to this kind of ensemble leave tonight suitably enchanted.