Most conductors will be used to the Universal Edition of Mahler’s works, which for this symphony was last revised in 1989 (second printing in 1995) by Sander Wilkens. For the most part, the Universal text has appeared a definitive and reliable edition – certainly far more so than the much more cheaply available Dover scores, based on earlier editions prior to Mahler’s copious revisions. I myself have various Mahler scores, most in Universal edition, including this symphony, which I last used in 2008. In both practical and musical use I found the new edition to be a far superior experience.

Practical Issues

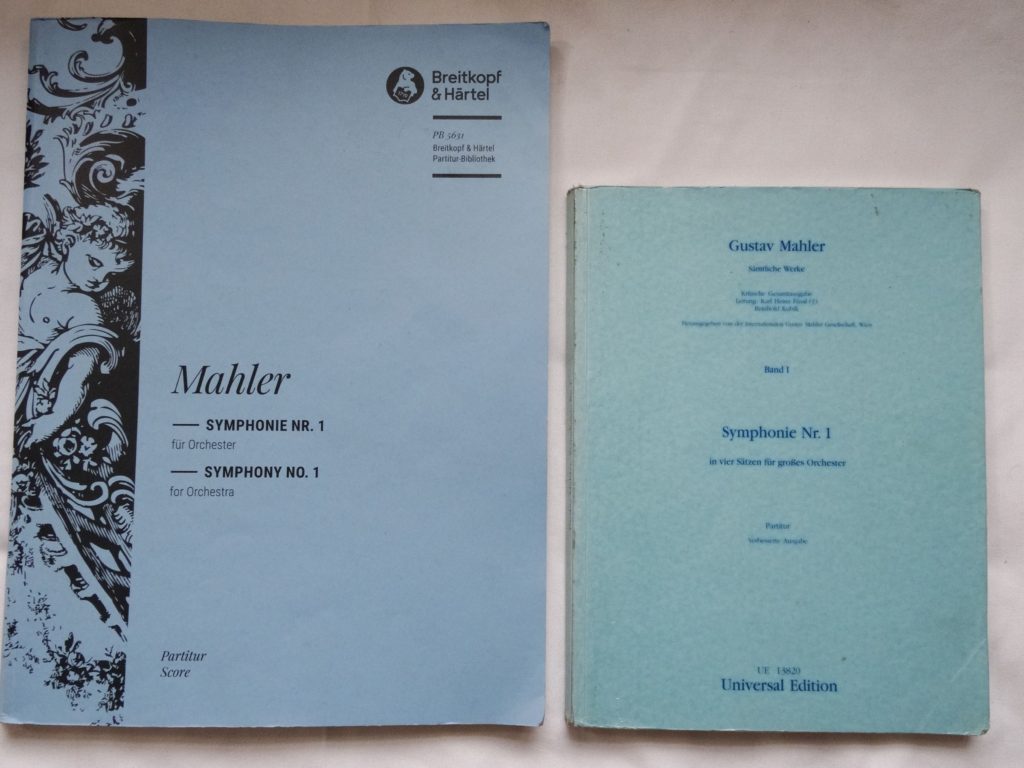

The Breitkopf edition is in B4 format – now my preferred size for a large orchestral score. It’s about a 1/3rd larger than the Universal Edition score:

For the size upgrade alone it’s a vast improvement. It’s far more practical for an orchestra of Mahler’s size and complexity than the Universal score, which is better suited for a Beethoven- or Mozart- size of orchestra.

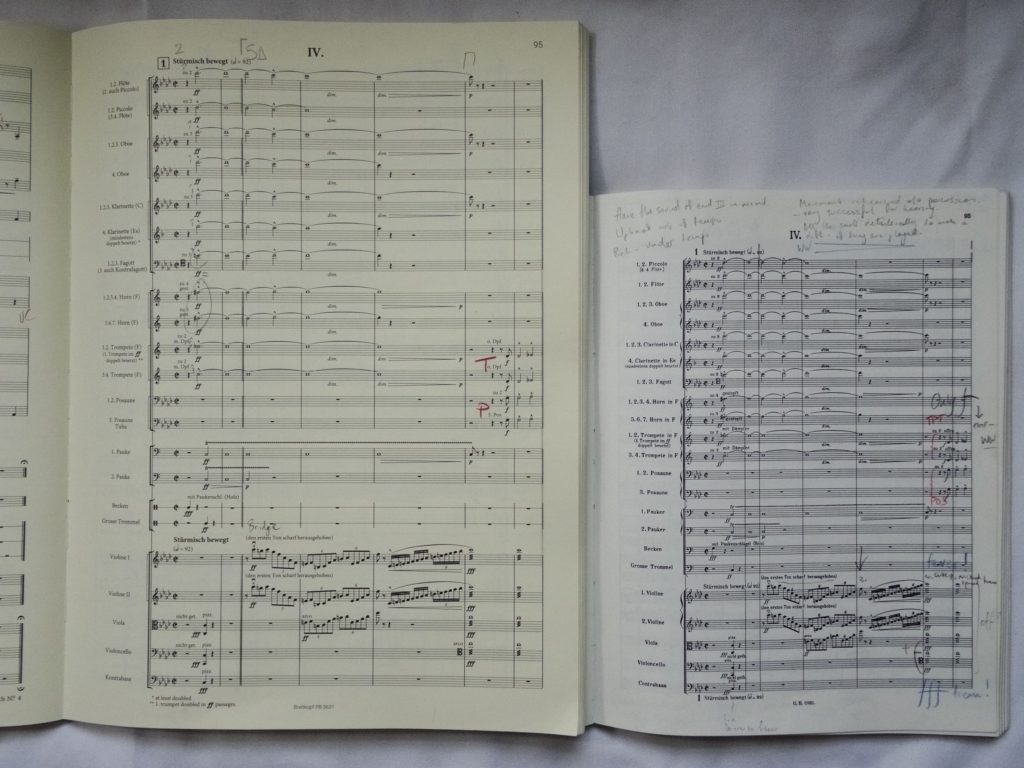

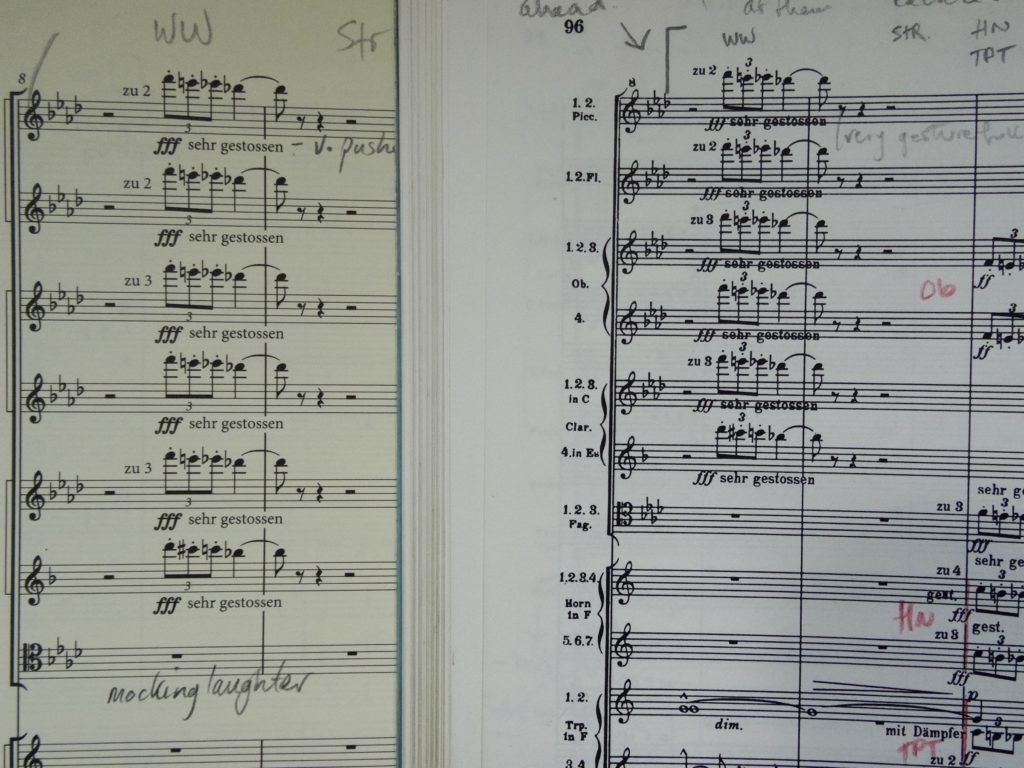

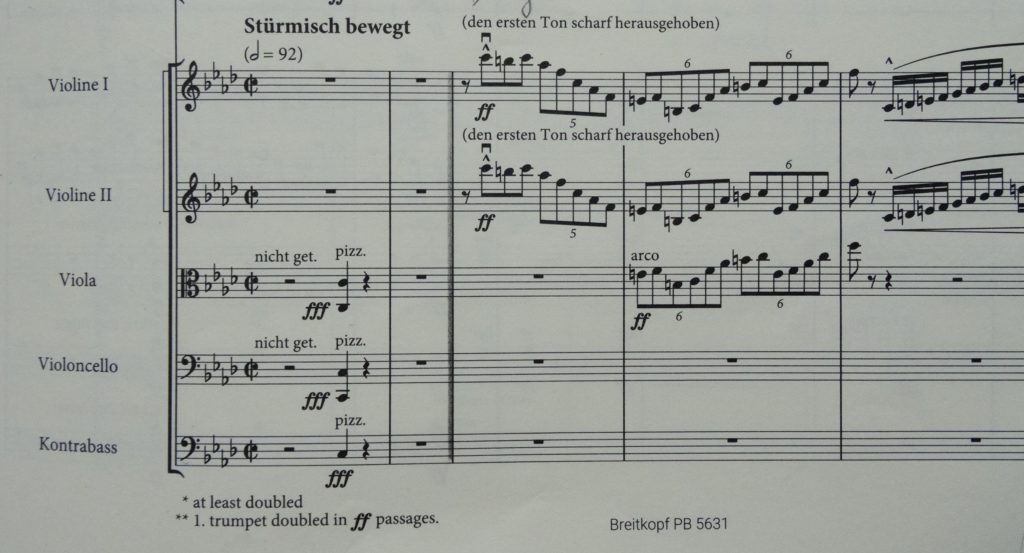

Secondly, within the larger format, the layout is much more friendly to the eye. In the Universal, the bar lines go all the way down the page. The new score has barlines linking instrumental groups, with gaps in between, making it much easier to see at a glance who is doing what. While I’ve still marked various things up to highlight structural features, it’s requires far less work to make immediate visual ‘sense’ of the score:

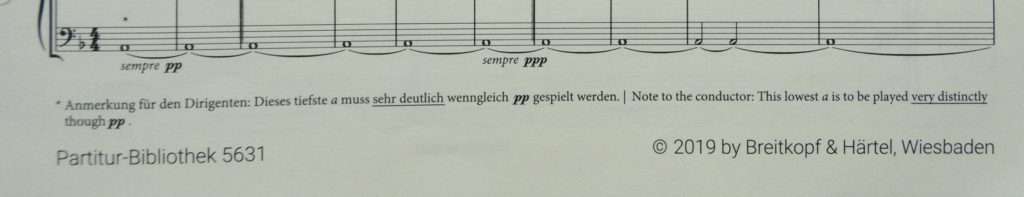

In an additional helpful touch, most of Mahler’s notes to the conductor are translated in to English at the bottom of the page. Where they are not, a copious glossary is provided at the back of both the score and the parts – Dover’s scores include a glossary for the conductor, but I believe this is the first time the individual parts have all had one.

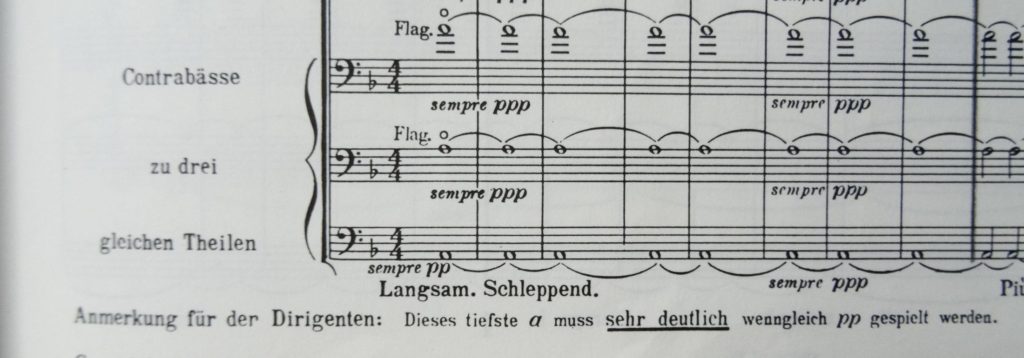

Universal Edition:

The larger size is also very well-spaced – mid-staff text is generally avoided (side-by-side with Breitkopf on the left and Universal on the right):

If only all Mahler scores were this clear!

The text

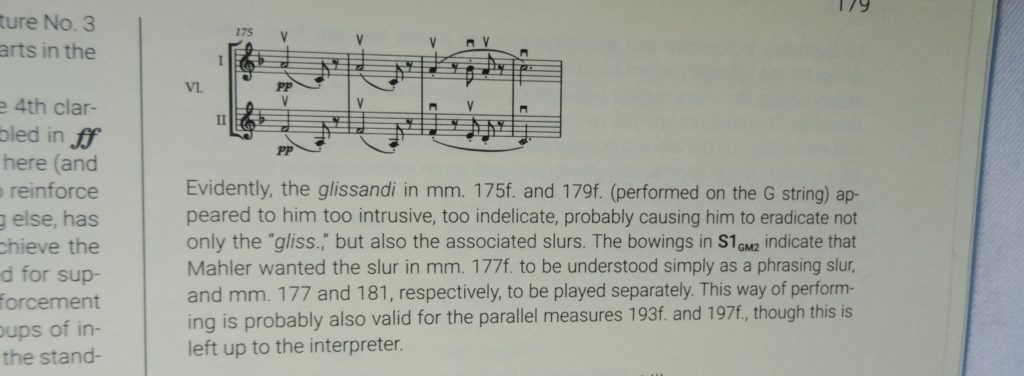

For this edition, which also includes a forward by the noted Mahler scholar Constantin Floros, editor Christian Rudolf Riedel consulted a total of 12 sources, including scores and parts, plus letters between Mahler and publishers and colleagues (such as Bruno Walter). Of these the final source is of particular interest: a set of first edition parts of 1899 from Mahler’s possession, which were used for the performance of the symphony under Mahler’s direction on 16 and 17 December 1909 at Carnegie Hall, New York. As Riedel explains: ‘the parts do not yet contain all of Mahler’s revisions […] but also contain, in part, other performance-practice indications and “retouchings”’. He goes on to state that ‘the parts are of interest despite or even because of their contradictions, granting an insight into the practical implementation of the composer’s intentions in the rehearsals. Adopting them in a text-critical edition appears, however, only reasonable in single cases.’

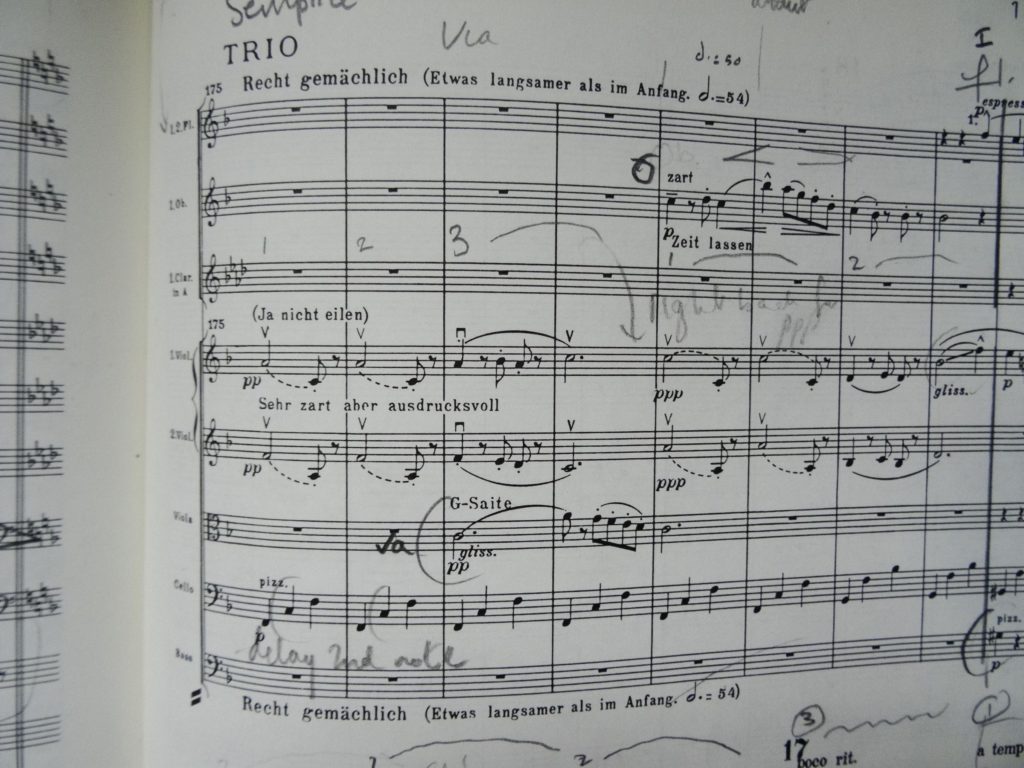

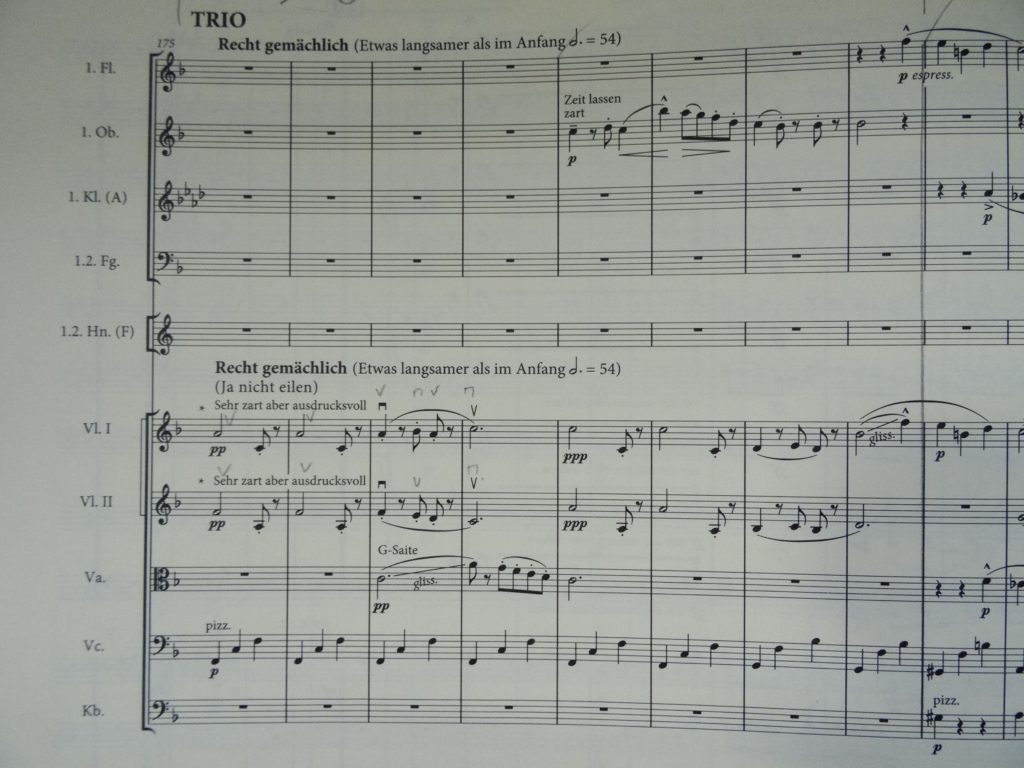

So essentially, he has taken a cautious approach to incorporating these new finds directly into the score, instead either inserting them as footnotes, or referencing the appendix. A good example of this is the beginning of the trio from the 2nd movement.

Here is Universal:

Compare the (lack of) printed violin bowings in the Breitkopf, plus the addition of glissando lines:

Plus the additional note in the editorial report including Mahler’s 1909 bowings from his set of parts:

An example of new information regarding doubling, based on Mahler’s correspondence (opening of IV):

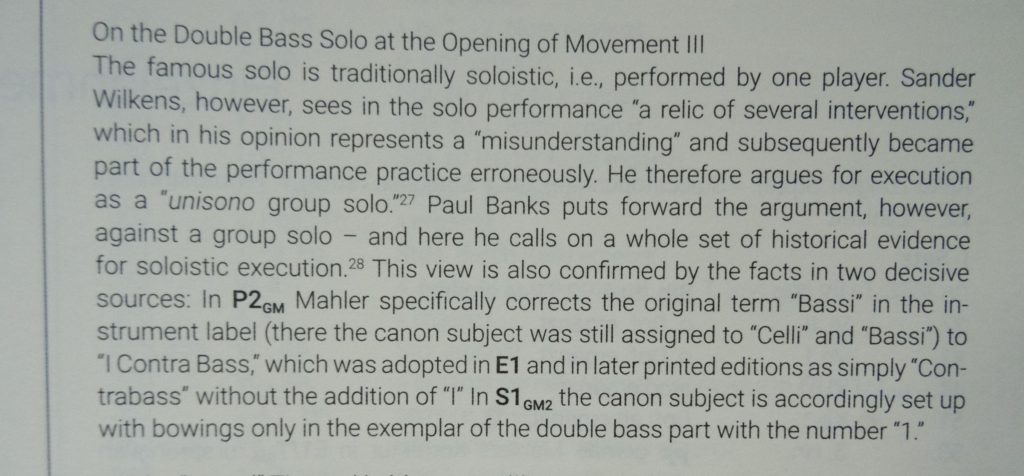

The Bass Solo

A brief word about the notorious issue of the double bass solo. For the Universal Edition, editor Sander Wilkens took the line that, contrary to usual practice, for the ‘solo’ written at the beginning of the 3rd movement, Mahler meant a solo for the section (unisono). Here Riedel argues cogently that it is, indeed to be performed by one player. As Mahlerfest Music Director Kenneth Woods has pointed out (referencing Paul Banks) – in addition, for all the recordings made by Mahler’s long-standing assistant and colleague Bruno Walter, this was always played as a single solo. If it was meant to be unisono, he of all people would have done it. I agree with this; as much as anything else, the sound of a lone bass playing high fits expressively in the musical argument in a way that a section of basses – nowhere near as exposed or fragile – or indeed awkward – would.

https://kennethwoods.net/blog1/2011/05/26/bass-solo-means-solo-bass/

Parts

Mahler’s orchestral parts are notoriously difficult for musicians to read, tending to be very closely spaced both vertically and horizontally. This can add significantly to rehearsal time in order to compensate for the difficulties in reading; and orchestral time is, of course , money. Time for a Mahler-sized orchestra is lots of money. The new Breitkopf parts are fabulously clear – well spaced, easy to read, and a great size. In general we found the page turns had been very well worked out. The paper is also of the highest quality – flexible enough for easy page turns, sturdy enough to stay on the stand even in their large format.

Breitkopf have been extraordinarily thorough in their proofing of this new edition. There must be in the order of over a million notes and markings in this score. Of these we found a handful of very minor errors, all of which have been passed to Breitkopf, and which will be corrected on the next print run.

All in all, this is a stunning score. By every measure it satisfies. I am very proud to have it on my shelf.

An alumnus of the inaugural class of the Mahler Conducting Fellowship, Michael Karcher-Young is Music Director of the London-based Beethoven Orchestra for Humanity, Assistant Conductor of the English Symphony Orchestra and Music Director of the Hereford Youth Orchestra.

An alumnus of the inaugural class of the Mahler Conducting Fellowship, Michael Karcher-Young is Music Director of the London-based Beethoven Orchestra for Humanity, Assistant Conductor of the English Symphony Orchestra and Music Director of the Hereford Youth Orchestra.

Karcher-Young previously served as Music Director of both London Youth Opera and Little Operations; founding Conductor of the Vanbrugh Ensemble and the Charities Philharmonia; and Principal Conductor of the Dorking Chamber Orchestra. He has also worked with the London Philharmonic, English National Opera and Grange Park Opera.

Michael began conducting whilst an undergraduate at the University of Leeds where he was awarded the Lord Snowden Prize for raising the profile of classical music at the university. Here he formed the Leeds University Union Symphony Chorus and established a series of charity concerts in aid of Cancer Research UK at Leeds Town Hall that continue to this day. Whilst studying postgraduate conducting, piano and harpsichord at the Royal College of Music, Kurt Masur awarded Michael the London Philharmonic Orchestra Conducting Fellowship and following this he became the Sir Charles Mackerras Fellow at Trinity Laban Conservatoire, London. Michael is a proud alumnus of Agnes Kory at the Bela Bartok Centre for Musicianship.

Recent and upcoming highlights include a performance of Tchaikovsky’s Pathetique Symphony with the National Orchestra Moldova, concerts with the English Symphony Orchestra (including Beethoven 5 in April 2019) and exciting new projects with the Beethoven Orchestra of Humanity.