Danube University Krems, Thursday 15 October 2020

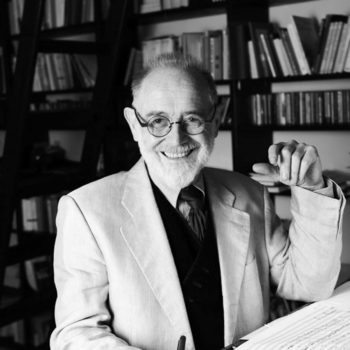

Peter Davison

‘How little is needed for happiness!’

(Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols)

I am privileged to have been invited to mark the 85th birthday of Kurt Schwertsik, one of Austria’s most respected living composers. When I have met him, I have been immediately struck by his friendliness, his modesty and good humour. He is genuinely interested in people and in life, managing somehow to avoid the divisive polemic so characteristic of our times. However, his instinctive diplomacy should not be mistaken for any kind of fuzziness in thought and action, as he lives by his values without stridency or preaching, accepting the validity of paths which are not his own. The breadth of his musical associations proves the point. Schwertsik is happy to champion his former teacher, Joseph Marx (1882-1964), whose richly coloured scores drip with impressionistic harmonies and emotional subjectivity. Yet he remains sympathetic to his late English friend, the dedicated Marxist, Cornelius Cardew (1936-81), whose main goal was to dismantle the conventions of bourgeois musical life.

I am privileged to have been invited to mark the 85th birthday of Kurt Schwertsik, one of Austria’s most respected living composers. When I have met him, I have been immediately struck by his friendliness, his modesty and good humour. He is genuinely interested in people and in life, managing somehow to avoid the divisive polemic so characteristic of our times. However, his instinctive diplomacy should not be mistaken for any kind of fuzziness in thought and action, as he lives by his values without stridency or preaching, accepting the validity of paths which are not his own. The breadth of his musical associations proves the point. Schwertsik is happy to champion his former teacher, Joseph Marx (1882-1964), whose richly coloured scores drip with impressionistic harmonies and emotional subjectivity. Yet he remains sympathetic to his late English friend, the dedicated Marxist, Cornelius Cardew (1936-81), whose main goal was to dismantle the conventions of bourgeois musical life.

Kurt himself enjoys being simultaneously a transgressor and a traditionalist. He acts like a spy in the camp, although we are never sure to which camp he belongs or for whom he might be spying. His triumph is that his allegiances may never be fully known, for he recognises that it is entirely human to want to be perversely radical and, at the same time, stubbornly conservative. Such fissures in the human psyche are a primary source for Schwertsik’s creative material. Like grit in the oyster, they are the product of tensions between his personal outlook and the wider cultural ambience. My presentation today aims to examine Schwertsik’s work in these terms. Specifically, I will explore the context of post-imperial decline in Austria and Britain, hoping to find significant clues to the cultural and psychological origins of Schwertsik’s music and its subsequent development.

Kurt Schwertsik has long been held in high regard in Britain, where he also feels very much at home. Many of the country’s finest ensembles and performers have commissioned works from him, including orchestras in London, Liverpool, Manchester and Glasgow. Schwertsik was also a featured composer during the 1993 Alternative Vienna Festival in London. His affinity with Britain may in part be explained because his mother was born in London in 1907. She was the illegitimate child of his Belgian grandmother who, while working in service, had a short-lived affair with her employer’s son, a young man called Charles Edward Hirst. These personal connections may have encouraged Schwertsik to befriend several talented Englishmen. Cornelius Cardew has already been mentioned, but Schwertsik owes much of his international success to the late David Drew1, who was his publisher at London-based Boosey & Hawkes until 1992.

Personal links aside, there is in any case a natural fellowship between the Austrians and the British, due to their shared experience of post-imperial decline. This instils in the culture of both nations an instinctively ironic worldview born from a feeling of unfulfilled destiny. In a postimperial context, the tone of discourse tends to be comical and nostalgic, rather than grand and glorious. Those trapped in slow decline hide behind polite masks but are prone to pessimism and self-mockery, since there is little to boast about and no great promise for the future. The outward persona may be filled with compensatory arrogance and aloofness, but guilt and oversensitivity lurk beneath the aristocratic veneer.

These common experiences and traits of character may partly explain why, to a surprising degree, the British concert-going public is so well-informed about Vienna’s musical legacy; from the classical masters, Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, to the experimenters of the Second Viennese School, Schönberg, Berg and Webern. The waltzes of the Strauss Family are also much admired, while many non-musical associations with Vienna remain fixed in the British collective imagination. The City’s labyrinthine sewers and the faded grandeur of its architecture provided a memorable backdrop to the film noir The Third Man (1949). The scriptwriter, Graham Greene, surely intended a parallel between the effluent poured into Vienna’s drains and the repression of shadow contents in the unconscious mind. Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), the psychologist who first exposed those dark secrets, is yet another Viennese icon. His musical equivalent can be found in the tortured confessions of one of Vienna’s best-known cultural exports, Gustav Mahler (1860-1911), now a staple of British concert life. Vienna, in the British popular imagination, encapsulates all that is contradictory about modernity2. It brings forth images of hedonism and opulence matched by an underworld of personal crisis and political extremism.

This ambivalent texture of horror and sentimentality, comedy and tragedy, anarchy and tradition are ever-present in Schwertsik’s scores. But, in one crucial sense he has rebelled against the Viennese tradition, making no apology for shedding the burden of historical destiny which weighed upon Mahler and Schönberg. Despite their Jewish origins, Mahler and Schönberg were inspired by the music and writings of Richard Wagner. In their younger days, both strongly identified with the Pan-Germanist movement. Neither man conceived the triumph of German art as a political project, but the values of German culture shaped their idea of what art should be. The artist must be colossally ambitious, seeking to change society and the course of history. Art must be a medium for the spiritual transformation of the individual, as well as a means for society to achieve cultural homogeneity. Placing such pressure on art and the artist was bound to intimidate those that followed in Wagner’s footsteps. Yet the roots of the problem went much deeper. The cult of genius surrounding Beethoven3 meant that every subsequent composer was expected to be a ground-breaking revolutionary and master of metaphysics. Obsessed by the towering achievement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, Anton Bruckner (1824-96) never developed much self-belief. He felt a similar inadequacy in relation to Wagner to whom he was devoted like a child. Then Bruckner was not alone in succumbing to the enchantment of ‘Old Klingsor’. Wagner dominated European culture for many decades, until the Nazi debacle created a moral imperative to lay waste to his magic castle.

In Austria, the post-imperial experience has many layers. The collapse of the Hapsburg Empire in 1917 ended a longstanding multi-cultural alliance of Central European States unable to find a balance between the national and ethnic tensions within its borders. However, there was a further failure of empire in 1945, which marked the end of the romantic dream of a Greater Germany. Because the Pan-Germanist movement had roots in German Romanticism and was associated with prestigious cultural figures such as Goethe, Wagner and Nietzsche, the end of empire was in this instance not only a crisis of tribal identity but also of cultural heritage. Art and music that stirred emotion, impaired rational judgement or which had nationalistic connotations was, after 1945, considered ethically suspect; a bourgeois hallucinogen obscuring barbaric drives and ill intentions. Instead, experimental modernism, banned by the Nazis and originating mainly from the serial works of the Second Viennese School, offered an effective antidote to Wagnerian flights of mythic fantasy. Yet, while the free dissonance of ‘modern’ music distanced it from Wagnerian aesthetics, the aims of this new generation of modernists was not so different in scope from their late-romantic antecedents. Revolutionary social critique, mystical spirituality and dogmatic aesthetic theories were just as central to their vision of the future as they had been for Wagner and his followers.

Peter Davison

Art music has never been as important to British cultural identity as in German-speaking nations and, compared to Austria, British post-imperial decline was less a series of crises, more a slow ebbing of confidence. When nations cease to believe in their exceptional destiny, they turn inward and to the past so that, around 1910, there emerged a nostalgic vision of Britain as a rural paradise, innocent and eternal, epitomised in Vaughan Williams’ Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis. The work was inspired by the choral music of the Tudor period, alongside the modal melodies and harmonies of English folksong. After the mass casualties of the First World War, this type of pastoral music became a source of national solace. The arrogance of empire could no longer be sustained, so that even Elgar’s swagger turned to elegy in his Cello Concerto of 1919.

After 1945, victory in the Second World War did not relieve Britain from the need to face dramatic social changes. Despite Churchill’s heroic leadership in wartime, a socialist government was elected to create the Welfare State. Old hierarchies and institutions were to be modernised to create a new Britain transformed by science and technology. In musical life, the patriarchs at the BBC and the Arts Council felt that this radical shift meant embracing international modernism, resulting in the marginalisation of a swathe of British composers who suddenly found themselves out of step with officialdom. An aesthetic revolution had taken place in which the concert-going public did not have much say. Many of the leading lights of this avant-garde movement were trained at The Manchester School of Music in the 1950s. There was Alexander Goehr4, who brought Germanic intellectual rigour to a culture ordinarily suspicious of theoretical systems. There were also two locally born talents, Harrison Birtwistle and Peter Maxwell Davies, who embraced the freedoms of atonality with enthusiasm, although Maxwell Davies would later revert to tonal writing. These figures were not heroic social idealists in the mode of Beethoven, nor stubborn resistance fighters like Schönberg. They were explorers seeking to prove that traditional tonal composers were flat-earthers bound by restrictive beliefs.

During the course of the last century, the notion that any composer might realistically aspire to world-historic significance in the manner of Beethoven or Wagner grew more and more implausible. Historical events had exposed the dangers of such idealistic fantasies. In our own times, a composer may only realistically aspire to personal authenticity. Beyond that, the artist has become increasingly powerless. In such a predicament, the composer is compelled to seek alliances with the like-minded, creating their own specialist ensembles and developing their own audience. Kurt Schwertsik soon discovered that solidarity and entrepreneurial spirit were valid responses to the collapsed cultural consensus. In 1958, he founded the avant-garde performing group die reihe with his friend, Friedrich Cerha. A decade later, no longer committed to modernist orthodoxy, Schwertsik worked with his fellow instrumentalists, H K Gruber and Oskar Zykan, to form the MOB art & tone ART ensemble. The latter group, according to Schwertsik, was dedicated to playing new works with broad appeal written in a tonal musical language. What is admirable about these composers is that they were willing to sacrifice personal ego for the sake of collaboration, while any divergence of musical style was tolerated without rancour. 5

If an artist accepts his marginal status, he must still find a purpose that will validate his work in wider society. There is a longing for the apparent certainties of the past. If only we could rediscover the visionary fervour of Beethoven or feel Mahler’s passion for truth! But today our cultural foundations are flimsy, and conviction is hard to muster, so that the composer must seek deep within himself for answers. In Schwertsik’s musical language, the invocation of a dream or fairy tale suggests a desire to reconnect with something lost to everyday consciousness; a bittersweet nostalgia for childlike innocence, for an idealised past, for certainties long gone. Schwertsik’s most Mahlerian work, his five-movement symphonic suite Nachtmusiken6 – Nocturnes (2009) was commissioned by the BBC Philharmonic in Manchester for a performance paired with Mahler’s First Symphony. Schwertsik’s music has haunting Viennese qualities, with its unashamed embrace of the sentimental and its witty even irreverent allusions to Mahler’s music. The first movement pays homage to Janáček and is entitled ‘Janáček ist mir im Traum erschienen’ – Janáček appeared to me in a dream. It is dominated by an angry rhythmic motto with a Slavic linguistic accent, typical of Janáček’s musical idiom. But the surging intensity of the music is more Mahlerian, as waves of pathos reach an ominous climax. In a Viennese context, the appearance of a Czech nationalist composer suggests a dialogue with the outsider or, in psychological terms, the wounded shadow is permitted to approach. This juxtaposition of Viennese and Slavic elements in Schwertsik’s work relates well to Mahler’s First Symphony, in which the narrative voice consistently identifies with the victim-outsider. We gain the perspectives of the hunted rather than the hunter, the peasant rather than the urban elite. The Viennese symphonic tradition is placed in opposition to Mahler’s complex cultural identity as a German-speaking, Bohemian Jew7. His rootlessness drives him towards the maternal consolation of Nature, thus away from musical and social convention. Schwertsik does not aspire to Mahler’s level of self-dramatisation, yet nonetheless the feeling of dislocation in Nachtmusiken is palpable.

I am reminded of a recent dream of my own set in Vienna in which I discovered an imaginary tunnel used by the painter Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) to reach the medieval centre of the City unnoticed. Klimt8, you may recall, antagonised the academic establishment with his infamous friezes for the University of Vienna in the late 1890s – Philosophy, Medicine and Jurisprudence– which were deemed too disturbing for the learned professors who did not wish to look up at dark symbols of repression and chaos. The controversy led to a heated political debate about the values and direction of Viennese society. It was a bruising encounter for Klimt who was forced to retreat, beginning his own dark transition which led him back to a quasi-medieval outlook in which dream, symbol, matter and consciousness became aspects of a single spiritualised reality. This was in sharp distinction to the post-Enlightenment world, in which reason, science and industrialisation, according to Freud, Klimt and their like, had divided the human psyche into warring parts.

Vienna’s grand facades, adorned by gilded classical statues, were built to convey confidence in the future based on the civilisations of the past, specifically those which had thrived through the application of reason. Modernity, above all else, meant the ascent of the rational man, a fruit of Christian virtue and neo-Platonic Idealism. In truth, modernity meant brutal engineering projects such as the railways that carved their way through the city’s residential areas and the rural landscape. Rational man and Nature were at odds. Vienna’s facade culture compelled figures such as the satirical writer Karl Kraus, the composer Arnold Schönberg and the architect Adolf Loos to strip away surface and ornament because they believed it obscured truth. This wave of modernism was an attack upon the socially optimistic narrative of modernity conceived by liberal progressives. Yet figures like Schönberg were always in danger of creating the very wilderness they were trying to prevent. Janik and Toulmin9 refer to the ‘polemical Puritanism’ of modernist ideology in the arts of the period. The rebels risked being as rigidly authoritarian as the social attitudes they were pitted against. Furthermore, modernist critique circa 1900 did not yet question the authority of the visionary genius. Artists sought to correct rather than destroy the bourgeois conventions codified by academic institutions and backed by the State. The primacy of the heroic genius, personified in the overpowering influence of Ludwig van Beethoven, continued to hold sway. The Exhibition of the Viennese Secession in 1902 included a celebration of Beethoven as an enduring symbol of creative freedom. He was memorialised in a statue sculpted by Max Klinger in which the composer was enthroned like an Emperor. Klimt also captured the Beethovenian spirit in his vivid frieze for the exhibition depicting humanity’s aspiration to joy and high ideals. The secessionists stood for idealism and were fighting against mediocrity, rigid academicism and ordinary human weakness. It was a battle they imagined could still be won, because artists believed it remained possible to change society through the influence of their work.

The decline of empire means an inevitable shrinking of central power and a weakening of faith in the future. This collapse impacts greatly on national identity. It leads to compensatory fantasies; sentimental dreams of making a country great again. Decline can be further reinforced by feelings of guilt and self-reproach for past colonial violations, cultural oppression, acts of slavery and other forms of commercial exploitation. The wider cultural response is inevitably ironic, because of the discrepancy between the outer shell of past greatness and the painful truth of a nation’s failure. Many choose to deny the fall, while others proclaim it with righteous indignation, and a few view it with just a wry smile.

Irony may be expressed with little more than a knowing wink or an inflection of the voice, but it can be savagely satirical. British humour after 1945, when empire was in terminal decline, gradually developed a distinctive irreverence towards an establishment still convinced of its right to rule. It culminated in the satire boom of the 1960s and the surrealistic sketches of the ‘Monty Python’ team. The entertainers who made up the group were exactly those who by background and education might otherwise have become the next generation of the ruling elite. They were highly educated and cultured Cambridge graduates, whose humour was not aimed at the working class but at disaffected young men like themselves. In the film, Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979), a satire set in Judea during the lifetime of Christ, the fragmented subculture associated with imperial domination is placed under scrutiny. Behind the bold facades and military muscle of imperial Rome, subversive Jewish factions argue among themselves. The general population is looking for a saviour to lead them to freedom and enlightenment, in this case an ordinary man called Brian who has been mistaken for the Messiah. The Roman overlords, who represent modernity, are portrayed as incompetent and ridiculous, while the rebels look to the past. The dissidents however cannot decide whether the benefits of Roman rule outweigh their loss of sovereignty. This could easily have been a picture of Britain10 in the late 1970s, still living the daydreams of empire, reluctant to accept that it was now merely an average-sized country in a fast-changing world.

The subversive antics of the Python team, which earned them accusations of blasphemy from leading churchmen, stemmed from the same cultural movement that made Cornelius Cardew into a musical anarchist. Cardew was a dedicated Marxist who penned the notorious article, Stockhausen serves Imperialism 11, repudiating the Darmstadt avant-garde as a further manifestation of bourgeois decadence. Cardew equated genius with the colonially expansive ego seeking to dominate the world:

Concurrent with the development of capitalistic private enterprise we see the corresponding development in bourgeois culture of the individual artistic genius. The genius is the characteristic product of bourgeois culture. And just as private enterprise declines in the face of monopolies, so the whole individualistic bourgeois world outlook declines and becomes degenerate, and the concept of genius with it. Today, in the period of the collapse of imperialism any pretensions to artistic genius are a sham.

Cardew had at first admired Stockhausen and the Darmstadt school but found its intellectual elitism politically and aesthetically distasteful. After dabbling in aleatoric and electronic composition, Cardew wanted music to return to its roots in real communities. This meant undermining the hierarchical institutions of formal society such as the orchestra, which kept music in the hands of a professional elite. He created the Scratch Orchestra which operated between 1969 and 74. The orchestra admitted players of any standard, amateur and professional, and it relied on improvisation. The experiment ended in acrimony as factions developed within the ensemble. Cardew was a longstanding friend of Kurt Schwertsik, having met in 1960 while working under Stockhausen’s supervision at the electronic music studio in Cologne. At the time, the pair had much in common as young experimental composers. But, as Cardew followed his own extraordinary path, Schwertsik did not allow ideological difference to be a barrier to friendship, nor cause him to deny Cardew’s substantial musical and intellectual influence.

For all that there was a lot of theatre and indulgent fantasy in the music of the 1950s avant-garde and in the ideas which sustained them, Schwertsik has always recognised the sincerity of their wish to redefine the boundaries of musical culture after the calamities of world war, the holocaust and the atomic bomb. Indeed, he admired Stockhausen12 as a musician and did not consider him a fraud, as did many critics of the day. Stockhausen was equally willing to tolerate Schwertsik’s doubts about the Darmstadt project. Yet ultimately Schwertsik did not feel he belonged to this disparate group of gifted musicians and intellectuals. They were building walls against the norms of musical life and thus the possibility of any real social engagement. Here his sympathy was with Cardew, but his solution was less anarchic. Schwertsik had, in his younger days, been a successful orchestral musician, and any iconoclastic instincts were tempered by realism about what audiences would accept and what musicians could play. He believed that abandoning all musical traditions, especially the expressive force of melody and the dynamism of counterpoint, would have opened irreparable rifts between composer, performer and listener.

Schwertsik’s hero, if that is the right word, is the eccentric French composer, Erik Satie (18661925). Satie was the trickster deflating Pan-Germanist egoism and Wagnerian excess, the hoaxer and social radical blurring the boundaries between life and art. In his modest way, Satie influenced several generations of composers including Debussy, Ravel, Stravinsky, the members of Les Six and even John Cage. His life and art intentionally mocked the grandiose attributes of the romantic genius. In the cantata Socrate (1919), Satie depicts through delicate understatement the death of an outsider; an autonomous individual executed for his wisdom and probing scepticism. Socrates is resigned to his fate, and there is no sense of grand tragedy. The powerlessness of the thoughtful man is accepted without defiant rage.

In the transition from modernity, perhaps there is to be no more cultural hegemony, no more supremacy for German, Austrian, British or any other kind of music. A composer may demonstrate rare talent but no longer be a genius. In a contemporary liberal democratic context, there is little space for the grand cultural project, nor is there the spiritual curiosity to risk exploring the great existential questions. It is now considered politically incorrect to aspire to cultural pre-eminence or display an ability or quality that suggests membership of an elite. There is even a danger that a cult of mediocrity will replace the former cult of genius. Vitality and ambition are the basis of all significant cultural developments, and no culture can thrive without such renewing energy. That said, excessive ambition and iconoclastic fervour can prevent an artist finding his authentic voice. His primary goal must be the discovery of his deep identity which transcends musical style, historical moment and contemporary fashion.

For all that Schwertsik is uncategorisable, he is not a post-modernist13 without allegiance to tradition. His outlook is close to Stravinsky’s, another of his eclectic musical influences. For both composers, tradition is an Urquelle or original source from which one may draw nourishment, but to which one is not obligated. Like Stravinsky, Schwertsik borrows from a wide range of sources, encompassing not only the classical masters of the past, but also jazz, cabaret and other forms of popular music which have caught his ear. In this manner, Schwertsik acknowledges that modernity has been a unique historical moment, but not a Utopian climax. Indeed, Vienna’s decline as a power-centre and its loss of cultural dominance have liberated him, allowing him to be open to wider influences. Schwertsik has found fields of activity beyond the polemic of entrenched political and aesthetic positions, seeking the intersection between his commitment to social ideals and his search for personal authenticity.

A consistent theme of Schwertsik’s work has been to give voice to Nature. Once he had abandoned his allegiance to Darmstadt, he was able to return to established symphonic forms and to rediscover the musical possibilities of tone-painting. In true Mahlerian style, the natural world could again provide a source of inspiration. Vienna’s proximity to rural landscape, the woods and hills which inspired Beethoven’s ‘Pastoral Symphony’, has meant that many of its artists have found in Nature a source of solace and timeless truth. In Schwertsik’s imagination, Nature is not always pretty or pastoral. It possesses a threatening but vital energy. His orchestral cycle Irdische Klänge – Earthly Sounds (1981) begins with a two-movement richly textured symphony which owes something to Stockhausen’s Trans for orchestra and tape, while also revealing debts to a variety of other musical sources, including Philip Glass, popular music, jazz and The Rite of Spring.

The Fünf Naturstücke – Five Nature Pieces (1984) that constitute Part 2 of Der Irdischen Klänge are more picturesque, especially the flowing lines of Wasser (Water) and the exuberant chatter of Vogel (Bird). The final work of the series is Das Ende der irdischen Klänge (1991), a single movement which concludes with a frightening side drum riff, as if Nature’s voice is silenced by human tyranny. Schwertsik’s most impressive work in this vein is Uluru (1992); a deeply felt response to the red rock which forms the most sacred site of the Australian aborigines. From nocturnal shadows, the dawn slowly awakens, culminating in a climax of Sibelian grandeur, as spirit once again seems to infuse matter. The aboriginal culture treats music as a song-line directing the life journey, where landscape and mind are two aspects of the same reality. For Schwertsik, the relationship with Nature is both personal and spiritual, a mirror to his own inner life and the wider human drama.

We have travelled a long way from the musical experiments of Stockhausen and the Darmstadt cabal, further still from Theodor Adorno’s pessimistic will to silence. Schwertsik says ‘yes’ to life, but this is no glib assertion. It demands a ceaseless search for meaning in a confused, crisis-ridden world. Kurt Schwertsik’s creative life has been a journey from Holy Fool to Wise Old Man, and his most recent works possess an inner freedom which suggests an artist with nothing to prove and nobody to please but himself. His suite of miniature piano pieces Am Morgen vor der Reise – The Morning before the Journey (2017) displays a Schumann-like inventiveness and fluency. Avoiding virtuoso display, he captures intimate and spontaneous feeling in a richly nuanced tonal language that sounds fresh yet familiar. A recent recording places Eden-Bar, Seefeld (1961), a short work for piano written in his Darmstadt days, alongside these lyric pieces. The texture is suddenly dissonant and fragmented, but the Schwertsikian moniker shines through regardless.

Friedrich Nietzsche, that contrary prophet of modernity, knew that liberation from the past risked hubris and moral collapse. He advocated reconnecting with instinct to discover once more the magnificent and tragic grounds of human existence. It was, he believed, the only way to escape the loss of vitality brought about by centuries of Christian guilt and Platonic idealism; an emphasis on rationality and abstract thought reinforced by the Enlightenment. According to Nietzsche, a revitalisation of European culture needed a return to the spontaneity of childhood, where humanity would no longer be constrained by conventional morality or thwarted by the hypocrisies of the adult world. Kurt Schwertsik has something of the eternal child about him, an unceasing curiosity and appetite for life. Yet, unlike a child, he does not shrink from the negative aspects of existence. In his public utterances, he has reminded us that ‘beautiful and ugly are categories for aesthetes’, and they should not constrain the artist14. Indeed, good music shows us that pleasure and pain, beauty and ugliness, comedy and tragedy are indivisible. In the Nietzschean sense, true joy lies beyond the polarities of ego, so we must accept the totality of our embodied existence despite its terrifying contradictions. We are compelled to stand firm before the extremes of human experience, yet the laws of harmony dictate that we must also learn to steer a skilful course between them. Nietzsche believed that music was essential to that end, because it can express in one note all that needs to be said:

‘How little is needed for happiness! The note of a bagpipe – without music life would be a mistake. ‘ 15

- Drew died in 2009 and is the dedicatee of the slow movement of Schwertsik’s Nachtmusiken composed in the same year. According to Drew’s obituary written by Alexander Goehr, he cherished Schwertsik’s music ‘like a caring gardener.’ See The Guardian, 2nd August 2009.

- It is worth noting the confusing terminology around modernism and modernity. Modernism tends to apply to the latest radical innovations of technique in the arts coupled with a progressive outlook. However, the concept of modernity suggests a climactic moment in history, when a progressive, liberal and largely optimistic vision of humanity prevails. Modernity is the moment when a society supposedly relinquishes barbarism, superstition and ignorance. Science, technology, democracy and academic study are intended then to lead to the completion of the human project. Creatively, artists have adopted many stances towards this Utopian fantasy. Some have responded with naïve enthusiasm, while others have allied themselves with the progressive ethos but sought to rebalance it with a dose of realism. A small group has responded with despair and anxiety, identifying with the suffering of Nature and the loss of instinct required to the reshape humanity. Some rightly perceive that modernity is not a uniform ideology but a phase of human development. The public itself is ambivalent towards modernity. While they accept that technological advance in general terms leads to social progress, they remain conservative in musical taste. Their cultural habits are motivated by a desire for reassurance to mitigate the pace of social change which otherwise leaves them breathless. During the 20C, modernity has served as both an inspiring myth and a curse of high expectations. The claim to be in the vanguard of modernity has often been used to conceal fading powers. The governments of the Communist Bloc, for example, were adept at making Utopian assertions in order to appear modern but, beyond some innovative agitprop and socialist realism, they did not support modernism in the arts because of its association with Western decadence and liberalism.

- One thinks of Benjamin Britten’s statement in a BBC radio interview in 1946 in which he stated that ‘“A certain rot, if that isn’t too strong a word, set in with Beethoven. Before Beethoven, music served things greater than itself. For example, the glory of God, the greatest glory of all. Or the glory of the state. Or the composer’s social environment. After Beethoven, the composer became the centre of his own universe.”

- Alexander Goehr was the son of the German conductor Walter Goehr who studied with Schönberg in Berlin. 5 In more recent times, the identification of Schwertsik, Gruber and Cerha as part of a Third Viennese School does not imply stylistic convergence. Such terms may help to consolidate generational shifts of taste and convention, but they tend to oversimplify stylistic differences. Composers are rightly suspicious of such categorisations. 6 The work received its premiere in Manchester on 16 January 2010, launching a festival celebrating Mahler’s 150th I was lucky enough to be present on that occasion and to meet the composer for the first time. 7 Mahler famously said. ‘I am thrice homeless, as a native of Bohemia in Austria, as an Austrian among Germans, and as a Jew throughout the world.’

- See Gustav Klimt: Painting and the Crisis of the Liberal Ego, pp.208-278 in Fin-de- Siècle Vienna, Politics and

Culture, Cark Schorske, Alfred A. Knopf, New York 1981,

- Wittgenstein’s Vienna, Allan Janik and Stephen Toulmin, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1973 p.262

- Britain easily morphs into Brian. Britain/Brian must accept that it/he are not exceptional (or no more so than any other country/individual). Brian is also the illegitimate son of a Roman soldier, something which he must conceal from the Jewish rebel group which he joins. Post-imperial Britain became increasingly multi-cultural, something which the die-hards of former British imperial influence found difficult to accept.

- Stockhausen serves Imperialism, Cornelius Cardew, originally published by Latimer New Dimensions Limited:

London, 1974.

- To average ears, the music of the post-war avant-garde, stripped of its revolutionary fervour, sounds incoherent and alienating. Perplexing as this music is, it is nonetheless an expression of human freedom, a desire to find meaning in what lies outside the normal bounds of cultural experience. The Darmstadt avant-garde provided a mirror to a fragmented world which many were reluctant to face. It was a mistake, however, to imagine that such music would ever replace or be treated as if it were the same as Brahms or Sibelius. At best, it sets the established repertoire in relief, although the practical challenges of presenting this music are considerable. There is an ‘all or nothing’ tendency about it, encompassing Stockhausen’s Gruppen for three orchestras (1957) and John Cage’s 4’33” of silence (1952). The contradictions become more apparent, when one understands that the avant-garde’s anti-bourgeois aesthetics are aimed at those paying for their privileges through public subsidies.

- Another confusing term, since post-modern indicates a collapse of modernist idealism but a continuation of its liberal attitudes and relativism. The true post-modernist believes that style is all there is and that the choice of style is entirely subjective. This is yet another Utopian delusion. The purest forms of minimalism are well suited to the post-modern context, because they lack obvious historical precedent and require little cultural knowledge to be enjoyed by the listener.

14Was and wie lernt man? Kurt Schwertsik, Verlag Lafite, Vienna 2020 p.217

‘Schön und hässlich sind Kategorien für Ästheten. Der Künstler arbeitet jenseits dieser Worte an der Verwirklichung seiner Vorstellung.’

15 Götzen-Dämmerung oder Wie man mit dem Hammer philosophirt Friederich Nietzsche, Leipzig, 1888

Maxims and Arrows No.33 ‘Wie wenig gehört zum Glücke! Der Ton eines Dudelsacks. – Ohne Musik wäre das Leben ein Irrthum.’ Nietzsche suggests that we should appreciate the down-to-earth realities of life without constructing elaborate philosophical fantasies of transcendence. In this same maxim, he infers that the German wish to make music into a metaphysical construct leads us away from spontaneous and simple pleasure. Der Deutsche denkt sich selbst Gott liedersingend. (The German even thinks that God is singing songs). Schwertsik too places great importance on the drone bass (Bordun) in the evolution of harmony and counterpoint. In Was and wie lernt man? (p.198) he writes: Das Besondere in unserer europaïschen Entwicklung scheint mir dass der Bordun sich zu bewegen began und als Basslinie schließlich ein Eigenleben gewann. (What is special about our European development, it seems to me, is that the drone began to move and finally gained a life of its own as a bass line.) He suggests that music evolves empirically from its simple roots i.e. what works for the ear, not as the consequence of musical theories and philosophical speculation.