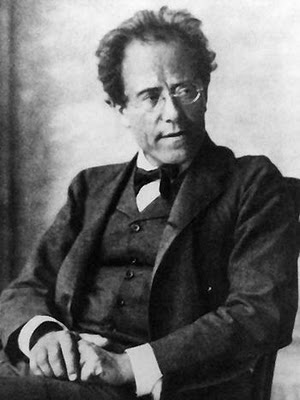

Join us on Thursday, May 14th for a complete performance with Stacey Rishoi – mezzo soprano, Brennen Guillory – tenor and Kenneth Woods conducting the MahlerFest Orchestra. It’s all part of our 2020 Virtual Colorado MahlerFest.

Some time I ago I was working with a very fine singer on Mahler’s Der Abschied (“The Farewell”) from Das Lied von der Erde. We talked a lot about color, about language, about tempo and about phrasing in all the music she sings. Then, to my mild surprise, she asked me about the music she doesn’t sing.

For readers who don’t know the piece, this song is about a half hour long. Almost dead center in the middle of it, the singer steps aside and the orchestra play a long funeral march, about six minutes in length. Her question was simple: what, exactly, is the purpose of this long march section?

Before readers start tittering at the notion of a singer’s bafflement at the idea that any composer would be daft enough to not have them singing while they are on stage, let me assure you it’s not just a good question, it’s a big question. It might be the biggest question in Mahler.

This is not the only such episode in Mahler’s music- there are similar long, march-like sections in the finales of the 2nd and 6th Symphony and in the first movement of the 3rd.

On first look, these sections can look a bit like fight scenes in movies. There are plenty of film fans who hold that all fight scenes in films are superfluous. All we need to know to understand the story is that there was a fight, and there was an outcome- we don’t really need to witness every kick, punch and shot. So too it seems with these great marches in Mahler- they don’t really advance the musical plot.

On the surface, Mahler looks very much like a “plot” composer. One reason so many people seem to be able to follow and enjoy these long, ambitious symphonies is the fact that they do have such a strong sense of musical storytelling in the way they are constructed. The first movement of the 6th Symphony is a model of classical concision- every bar is part of a single, direct, completely logical narrative- almost the opposite structure of the Finale of the same work, where Mahler let’s a sort of almost uncontrollable transformative energy run wild as nowhere else in music (ever the master of paradox, this movement is also his most motivically taut). This impression is strengthened in a work like Der Abschied, where the singer is narrating events for us from the beginning of the song. Suddenly, it is as if the narration says “and then, I marched…. I marched and marched and marched and marched. Sadly. For a long time. Marching. Sadly….” Then it goes on describing the marching for several more minutes. In the 6th Symphony Finale, you can substitute “defiantly” for “sadly.” In the 2nd, you can say “ all humanity dead and alive marched, and marched and marched.”

It all sounds a bit miscalculated or self-indulgent. But, ask any Mahlerian, and they’ll tell you these passages, which, strictly speaking, don’t have to be there, which some would say shouldn’t be there, are some of the most telling, moving and transformative in all music.

You see, while on the surface, it seems that these great marches are just along elaboration of the statement “I/he/she/we marched,” they actually serve a profound purpose in his music. They embody the idea of the transformative power of time, expectation and process. You can pick your metaphor- clay baking in an oven, 40 days and nights in the desert, the caterpillar metamorphosing into a butterfly in the cocoon, or the baby gestating in the mother. When we hear this music performed well in a setting that allows for a strong connection between music, musicians and listeners (sometimes, when all goes to plan, the musicians are listeners, too), we can feel that although nothing obvious has happened to advance the musical plot in the last 7 minutes, some profound transformations have occurred. We feel changed by what we have experienced. If I could articulate what that change is, we wouldn’t need Mahler.

Mahler didn’t invent this phenomenon. There are many great works that combine a strong storytelling aspect with an underlying or hidden process of deep emotional transformation. Bach’s St Matthew Passion tells a very familiar story, but I always feel in the final chorus that all the time we’ve been doing more than just following the story of the Crucifixion, powerful as it is. Bach has been letting another, deeper, subconscious process unfold. Something about the hypnotic rhythm of the mixture of narration, contemplation and chorale, again something which seems like artifice rather than being dramatically essential on first glance, gives the whole work a sense of slowly working power. It’s like being rolled over, in a nice way, by huge slow waves of the ocean.

I suppose what sets Mahler apart from his predecessors is the way he is so blatant about just announcing to the listener, “sit back in your chair, forget about getting anywhere soon, and I’m going to re-wire your soul for about 10 minutes.” Dmitri Shostakovich certainly saw what Mahler was up to. The so-called “invasion theme” in his 7th Symphony (the Leningrad) is a particularly brazen version of creating a vast part of a piece that on one hand seems to serve no purpose at all, but which somehow works a powerful transformative process on the listener over time. Some critics whose preconceptions and prejudices overpower their perception see the lengths to which Shostakovich goes to achieve scale in the 7th as an indication of a weakness or technique, judgment or inspiration. They say the long passages in the first and third movements where nothing seems to happen for ages are an indication of the lack of the material or a failure of judgement. Trust me, if Shostakovich had wanted to write an event-packed, developmentally engaging development section to the first movement of the 7th Symphony, he could and would have. The whole point about a transformative episode like going into the desert for 40 days and 40 nights is that not a whole lot is supposed to happen. Switching metaphors again, once you put the stew in the pot, you don’t keep chopping onions and browning beef- you have to let it simmer. You have to let transformation run its course.

Again, Mahler didn’t invent catharsis, nor transformative moments, but part of sets his symphonies apart from, say, Beethoven’s is the way in which Mahler mixes the traditional tautness of sonata form, with all it’s storytelling qualities (something he shows he can do without deviation in the first movement of the 2nd, 4th and 6th Symphonies), with music that stands apart, music that meditates, that slowly and methodically re-wires our insides.

If you ask me the question “Why Mahler,” I might give you 100 different answers on 100 different days, but perhaps this is the aspect of his music that means the most to me. After all, these explicitly transformative episodes are only one aspect of something that is at work in all his music. Even as one follows the surface level of the music in all its richness and complexity with complete attention, another, deeper, more mysterious level of the music is working its magic on you.

There always passages, even whole movements, in Mahler that don’t seem to need to be there. Does the 3rd Symphony really need all those short movements between the first movement and Finale? Surely the contralto song would be enough- do we need all those bimm baums? Doesn’t the opening of the Finale of the 1st Symphony go on longer than it needs to in order to make its point? Everyone knows the Scherzo of the 5th Symphony could use a few cuts. The first 15 minutes of Part II of the 8th Symphony don’t seem to need to be there. All of these, and many other passages, like the march in Der Abschied, seem less than essential.

But Mahler, always the master of paradox, knows that what often seems extraneous can prove to be indispensable. He knows that somehow all those short movements in the 3rd give us time to absorb and contemplate what we’ve heard in the first movement, and prepare us for the timelessness of the Finale. Even while I’m listening to Bimm Baum and wondering what on Earth he was thinking when he wrote it, something inside me is changing, is being changed. He knows that the ending of the First Symphony will sound trite and facile unless we really have been battered by the music that precedes it- when the horns stand, it should be the gesture of a bloodied and bruised group of heroes, not the cocky assertion of arrogant, triumphant youth. He knows that what seems the most extraneous is often the most essential, that the key to making a huge drama hang together is knowing when to step away from it.

This is why we turn to Mahler’s music not just when we want to listen to some good tunes, but when we need something deeper- consolation, catharsis or transformation. This puts Mahler’s music in exalted company- we can listen to it anytime, but turn to it in times of personal or social crisis in the same way we turn to late Schubert, Bach, late Beethoven and the most exalted pages of Mozart. Of all of these voices, Mahler’s somehow seems the voice of our time- his life seems somehow more familiar than those of Schubert and Beethoven, as does his death.

And, after all, his death 100 years ago was played out just like one of these episodes in his symphonies, or like the middle section of Der Abschied. The story could just be- “then he died,” but the story of Mahler’s death is long and detailed, without being “dramatic.” He knew the inevitable outcome when his last illness was diagnosed, and yet the whole world watched the slow process unfold. Just as Mahler the composer is never content to tell us “they marched,” but must always show us how long they marched for and how much they suffered, so in the impossibly close connection between his music and his life, he shows us not only that he died, but how he faced death, from an idea to an inescapable reality to a finality, but even then, in his music, to a doorway. Just as “they marched, and marched, and marched,” Gustav Mahler, composer might have composed that Gustav Mahler the man “died and died and died. He started dying when his heart condition was diagnosed, then died a little more when his wife cheated on him, then died a bit when the politics of the Viennese and New York musical power structures humiliated him, then started dying in earnest in New York, died a bit more on the ship sailing back to Europe. He died for a bit in Paris, then continued dying on the Orient Express, and finally finished dying in Vienna, while the musical world looked on in voyeuristic fascination.” Except that all the time, he was fighting back with all his strength, living with a vengeance. Creatively, Mahler milked his own death for all it was worth, and yet, as a person, he never confused acceptance with surrender.

On the first tam-tam note of Der Abschied, Mahler wrote “death knell.” It’s not a promising start to a 30 minute movement. Why do we want to listen to a 30-minute song about a protagonist who is already dead? Why not just say- “he died” rather than “he died and died?”

Why is that long march sitting there in the middle? Because music is not a statement of fact, but an experience in time.

Richard Strauss is reported to have said in his final hours that “dying is just like I composed it in Death and Transfiguration.” Hopefully, Mahler had composed himself an even better death, and that when his final breath left him in that hospital in Vienna, the horizons brightened blue in the distance, forever.