As a young musician for whom the music of Mahler was the most remarkable and unexpected discovery, I never thought that performances of his music would become so frequent and routine that music industry colleagues would begin to speak of “Mahler fatigue.”

Although the post-War evangelism of Leonard Bernstein, Bruno Walter and Otto Klemperer had done much to raise awareness of Mahler’s music on record, performances of his music remained exceedingly rare, and limited almost entirely to major orchestras in big cities, until well into the 1990’s. I can’t remember our local professional orchestra ever doing a piece by Mahler when I was growing up.

Although the post-War evangelism of Leonard Bernstein, Bruno Walter and Otto Klemperer had done much to raise awareness of Mahler’s music on record, performances of his music remained exceedingly rare, and limited almost entirely to major orchestras in big cities, until well into the 1990’s. I can’t remember our local professional orchestra ever doing a piece by Mahler when I was growing up.

My goodness, how things have changed.

Mahler’s music has now seen a huge explosion in popularity and accessibility. Long a fixture at major festivals and international orchestras, his music can now be heard every year in performances by regional orchestras, youth orchestras and amateur orchestras.

Is this the natural culmination of a century-long campaign to raise awareness of this incredible music, or too much of a good thing?

When I took up the role of Artistic Director of Colorado MahlerFest, this sea change posed an existential question for us. My predecessor, Robert Olson, founded the festival in 1988 because, at the time, Mahler’s music was almost a complete rarity in that part of the country. With the festival now in its 33rd year, the dozens of orchestras along the front range of the Rocky Mountains almost all do a Mahler symphony every season. Has MahlerFest become obsolete?

I made two decisions early on. First, that given that Mahler has gone from being a largely unknown composer to one of the most popular, we ought to use his new notoriety to help raise awareness of similarly deserving composers whose music currently languishes in the kind of obscurity that Mahler’s did 50 years ago.

And second, I wanted to make MahlerFest an antidote to “Mahler fatigue.” Each year’s festival is built around a single performance of a Mahler symphony, and every talk, class, recital or concert that happens during the festival is all designed to set that Mahler work in the most inspiring context possible. In a typical festival, we not only welcome leading Mahler scholars from all over the world to speak about the music, we program works that Mahler quotes from or references in his own music, as well as music that was influenced by the Mahler symphony at hand. We might couple a work by Mahler with one from another composer facing similar personal or artistic challenges.

We also allow ourselves more rehearsal time than one would normally have to dig deeply into the unwritten language of Mahler’s music. There are many paradoxes in Mahler, and one is that he writes more on the page than almost any composer, and yet, to do his music justice, one needs to understand how to stylise rhythms like waltzes and marches in an idiomatic way that can’t be written down.

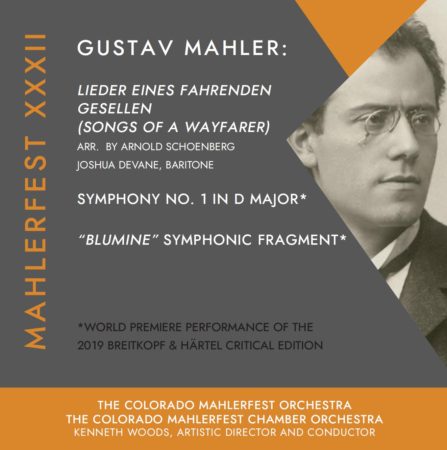

Last year’s festival felt like a turning point in our efforts to build this new MahlerFest. Following an unforgettable week of chamber concerts and recitals, our final orchestral concert opened with Mahler’s orchestration of Beethoven’s Leonore Overture No. 3, an invaluable window into Mahler’s persona as a conductor. We followed with the gorgeous Violin Concerto (dedicated to Alma Mahler) by Erich Wolfgang Korngold, the former child prodigy who grew up in Mahler’s Vienna. We then concluded with the first performance of the new Critical Edition of Mahler’s First Symphony published by Breitkopf and Härtel. How exciting it was to be able to give a premiere of something by Mahler in the age of Mahler fatigue.

Change is, of course, life’s one constant. Since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, performances of Mahler’s music have, like almost all music, stopped entirely. We had spent the last year planning a festival for this May which we were sure would be the most ambitious and inspiring we’d ever delivered. Cancelling those plans was heart-breaking.

After long months of silence, the world’s orchestras are now starting to awaken. My own orchestra, the English Symphony Orchestra, are beginning a series of studio concerts this month, and Mahler’s music will figure, although in an arrangement for chamber forces. Large-scale choral and orchestral works like Mahler’s 2nd, 3rd and 8th symphonies will probably be the last facet of musical life to return to our concert halls.

We plan to do the 2nd and 3rd symphonies at MahlerFest in our next two festivals, if it is safe to do so, and I really can’t imagine a more moving moment than to hear our chorus sing “Aufersteh’n” for the first time. Our job in the next 20 years is to remember how precious and fragile the ecosystem is which makes these moments possible, and to protect it and nurture that sense of occasion every time Mahler’s music is on the stands with orchestras everywhere. I think it will be a long time, however, before we have to worry about Mahler fatigue being a problem again.