“Come! Raise yourself to the highest spheres”

Mahler’s Symphony No. 8 in E-flat

“Symphony of a Thousand” (1906-7)

“It [a gift-copy of Mann’s Royal Highness] is…a mere feather’s weight in the hand of a man who, as I believe, expresses the art of our time in its profoundest and most sacred form.”

Thomas Mann (in a letter to Mahler after the première of the Eighth symphony)

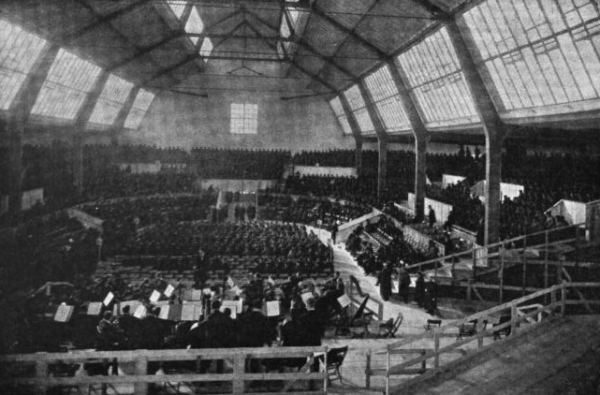

Mahler in rehearsal for the premiere of his Eighth Symphony

After the ambiguities and ironies of the Seventh Symphony, Mahler returned to a project that had been gestating in his mind for many years. An early sketch of the Eighth Symphony reveals a structure that was more conventionally symphonic than the two-movement choral cantata now familiar to us. There were to be four movements, starting with the Veni Creator, followed by a movement called Caritas, then a scherzo based upon children’s games at Christmas and a finale titled Creation through Eros. The Caritas movement looked back to early sketches for the Fourth Symphony dating from 1896. These outline plans demonstrate how the Eighth Symphony provides the musical and intellectual bridge between the Wunderhorn symphonies and the mid-period trilogy; the symphonies five, six and seven. The work also represents something quite unique in Mahler’s creative development.

The Eighth Symphony is typical of Mahler’s inclination to bring unlikely sources together. It combines settings of the Latin Hymn, Veni Creator Spiritus with an extract from one of the defining masterpieces of German Romantic literature; the final scene from Part II of Goethe’s Faust. The symphony is quite simply about Love. As Mahler wrote to his wife in 1910:

The Eighth Symphony is typical of Mahler’s inclination to bring unlikely sources together. It combines settings of the Latin Hymn, Veni Creator Spiritus with an extract from one of the defining masterpieces of German Romantic literature; the final scene from Part II of Goethe’s Faust. The symphony is quite simply about Love. As Mahler wrote to his wife in 1910:

“The essence of it is really Goethe’s idea that all Love is generative, creative, and that there is a physical and spiritual generation, which is the emanation of the Eros. You have it presented symbolically in the last scene of Faust…”

The work is a musical realisation of this idea of a single creative force, Eros, which develops from the physical to the spiritual. Mahler also draws upon Goethe’s image of the “Eternal-Masculine” that struggles for meaning and knowledge, but finds fulfilment only in being received by the “Eternal-Feminine”, thus revealing that creation comes from the relation of opposing but complementary energies; a pattern most apparent to us through our experience of human sexuality.

To understand the radical implications of the Eighth, it is necessary to understand how Mahler’s notion of Love differed from conventional attitudes and beliefs. Over many centuries European culture has tended to suppress Eros, the feminine principle. Despite notable moments of exception, such as the medieval tradition of courtly love and recurrent periods of Marian worship, the Church has generally emphasised Logos, the word as law, rather than the irrational aspects of religious belief. A religion that relies on feeling is much less easy to control than one governed by dogma, so those in positions of authority have preferred to persecute pagans and other dissenters. In fact, all the great monotheistic religions incline towards patriarchy, and many organised forms of Christianity have the stamp of male chauvinism. As Western societies have developed, this bias has been compounded. During the Enlightenment, Nature became demonised as the source of dangerous instincts opposed to virtue and civilisation, while the Industrial Revolution encouraged the ruthless exploitation of the Earth to advance prosperity. In this context, Mahler’s adoration of Woman and his religious responses to Nature set him apart from the prevailing collective attitude, aligning him with the counterculture of the romantics.

For religious thinkers outside of the mainstream like Carl Jung, the spiritual journey of modern Man is a search for his lost soul which has become trapped among the suppressed debris of collective compromise. No work of art illustrates this idea better than Goethe’s theatrical masterpiece, Faust (Part I, 1808 & Part II, 1832). In this epic myth Mephistopheles offers to help Faust win dominion over the world but, if at any moment Faust believes he has achieved the ultimate happiness and ceases to strive, his life will be forfeit. The devil appears to Faust when he is feeling most negative and is thus easily able to seduce him into replacing faith in God with the idols of power and knowledge. The wager is an invitation to inflate Logos at the expense of Eros, and by accepting this offer Faust adopts the pervasive materialistic outlook of the post-Enlightenment world.

Goethe portrays Faust as an incomplete creature striving for admiration, power and wealth. It is not an unsympathetic account, even though Faust inflicts suffering on others, especially the vulnerable Gretchen whom he recklessly spurns. Later, when Faust is a successful and brilliant man married to Helen of Troy, he finally loses his bet with the devil in a moment of self-satisfaction. His life is over. In the final scene of Part II, the episode adapted by Mahler for his Eighth symphony, Faust’s former lover, Gretchen returns to redeem him through her unconditional love. At the end of the play, it is the Eternal-Feminine or Eros which saves Faust from himself and inspires him to continue growing towards spiritual enlightenment. The Eternal-Feminine constellates an image of perfect beauty, stirring desire through her promise of transcendence. She represents the well of life; a source of healing, and she is also the call of destiny; the lady of fates. The Eternal-Feminine is in essence the idealised image of a man’s soul. Goethe’s vision of a man reunited with his soul chimed with Mahler’s own longing for inner transformation and his own vision for transforming the culture around him.

By contrast with Mahler’s pre-occupation with a redemptive and feminised religion, the cultural atmosphere around him was characterised by the decaying vanities of Habsburg Vienna. It was a society where facades and excessive ornament concealed corruption among the ruling classes and sanitised a harsh reality for ordinary people. Many intellectuals of the day wanted to expose such falsehoods by rebelling against superficial appearances. The philosophical rigours of Ludwig Wittgenstein, the austere architecture of Adolf Loos and the biting satire of Karl Kraus were all manifestations of this passion for truth-seeking. Mahler’s music had similar “modernist” qualities, but unlike many of his contemporaries, he never relinquished the quest to express beauty and to comprehend the sublime. They remained the goals of his work and, even if he wished to expose the false and the ephemeral, he continued to long for an experience of transcendence which would restore his faith. For this reason, Mahler speaks to us today with striking relevance about our own struggles for spiritual certainty and enduring values. The symphonies five, six and seven have a critical mode of expression with their ironical gestures and self-conscious approach to convention, but in the Eighth, with its huge choral forces and debt to Goethe, Mahler reconnected with the extroverted Romanticism of his earlier symphonies, even evoking past settings of the same text by Schumann and Liszt.

Despite the traditional idiom of the Eighth, the technical advances of the work over its immediate symphonic predecessors are still apparent. The symphony is innovative due to its eclecticism, which encompasses Baroque oratorio, Classical sonata, Lieder and Grand Opera. These are self-conscious allusions and the various genres assert glorious traditions which were dangerously close to being subsumed in the chaos of contemporary urban life. The Viennese author, Robert Musil (1880-1942), captured such an image of “modern” living in his novel, The Man without Qualities (Part I, 1930), in which “the City” symbolises the impersonal economic forces and social pressures that produce a spiritual vacuum:

“Like all big cities, it consisted of irregularity, change, sliding forward, not keeping in step, collisions of things and affairs…of one great rhythmic throb and perpetual discord and dislocation of opposing rhythms…”

Mahler’s Eighth symphony was an act of spectacular defiance; a clinging to order, to traditional values in the face of dehumanising processes of industrialisation and mechanisation which would lead eventually to the catastrophe of the First World War. The work possesses a spiritual optimism which subverted the chaos, decadence and pessimism of its times.

The story of the composition of the Eighth symphony, as told by Maher’s wife Alma, suggests that the opening movement came in a blinding flash during the summer of 1906.

“After we arrived at Maiernigg…he was haunted by the spectre of failing inspiration. Then one morning just as he crossed the threshold of his studio up in the wood, it came to him – “Veni Creator Spiritus”. He composed and wrote down the whole opening chorus to the half-forgotten words.”

Within a matter of weeks, the whole massive structure of the symphony was drafted. However, the idea that the Eighth symphony appeared quite spontaneously is misleading. It emerged from many years of preoccupation with the concept of Eros as a redemptive force, and there are thematic connections to the works that preceded the Eighth, especially the Seventh Symphony.

The completed work was not performed until September 1910 in Munich, by which time, Mahler’s life had taken a tragic turn with the death of his elder daughter and diagnosis of a potentially fatal heart condition. His marriage was also in crisis, and a month before the première Mahler was compelled to meet with the psychologist, Sigmund Freud for a walk along the canals of Leiden in Holland. It was an appointment intended to help him relate better to his young wife, Alma who had embarked on an affair with the radical architect, Walter Gropius. Her liaison had been the consequence of stresses in the marital relationship. Freud diagnosed Mahler as suffering from a negative mother complex and that he was projecting an idealised image upon Alma which did not recognise her real needs and wishes. In an attempt to make amends, Mahler dedicated his Eighth symphony to her, although this perpetuated her role as the servant muse, and Alma was not eager to accept the dedication.

For Mahler, Alma embodied the Eternal-Feminine, and his love for her was generated by an intense projection of his own soul. Her fall from perfection had wounded him all the more, because he needed her to be his all-forgiving Gretchen, drawing him towards the sublime through the force of her unconditional love. Of course, the Eighth Symphony is about much more than Mahler’s obsession with Alma. It concerns humanity’s need to rediscover the feminine principle as a redemptive and healing archetype which leads us intuitively towards the divine. Mahler’s symphony shows us how the divine inspires us through love and awakens us to creative possibility. It shows how we should respond to that gift with common spiritual endeavour by building a Holy City where we are bound emotionally and spiritually to those around us. The symphony also illustrates what happens when the divine gift is squandered by the pursuit of power, and how that grace can be restored.

The dress rehearsal for the premiere of Mahler’s Eighth Symphony, conducted by the composer, in Munich in 1910

Despite his many troubles, Mahler was temporarily reinvigorated by the première, and he won the hearts of the great mass of performers, especially the 350 members of the children’s choir, who adored him. The work was rapturously received by an audience of three thousand. While the first performance of the work involved precisely 1029 performers, in reality the work can be staged quite adequately by less than half that number. The orchestra usually totals well over one hundred with quadruple winds and brass, two harps, organ, harmonium, piano, celesta and mandolin, plus a large body of strings and a battery of percussion. There are parts for an off-stage brass band, eight vocal soloists and a double chorus and boys’ choir. The work is under any circumstances a huge undertaking.

The first movement, Veni Creator Spiritus – Come, creative spirit, opens with a burst of vitality held together by the disciplines of sonata form and fugue. The double-chorus represents Man as a social and collaborative creature giving form to the creative spirit.

The textures of the music are vigorously contrapuntal, after the initial invocation of the divine. The main theme is characterised by the leap of a seventh and a dotted rhythm, which become the thematic seeds of what follows. In a more fluently lyrical section, the soloists lead a plea for grace (Imple superna gratia). Fleeting allusions to Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnburg remind us of another great work which places music at the heart of the community. There is a brief moment of doubt, with a reflection on the weakness of the body (Infirma nostri corporis), before the strings rise to ethereal heights and the light returns (Accende lumen sensibus), firstly in serene mood, then with another great exclamation by the full chorus. This leads into a strident fugal development section which asks God to drive the enemy from us to avoid disaster (Hostem repellas). The fugue rises to a massive climax and a reprise of the opening, scored more exuberantly than ever. In an explosion of Pentecostal joy, the movement races towards its conclusion in a Gloria which also acts as the movement’s coda.

Part II of the symphony is a setting of the final scene from Goethe’s Faust, where Faust is redeemed by the love of Gretchen from his pact with the devil. The mystical imagery of the text depicts the completion of a spiritual journey; the attainment of the redemptive ‘Eternal Feminine’, “the resting place, the goal“, as Mahler described it. The contrast between the two parts of the symphony is often met with puzzlement, because the juxtaposition of a Latin hymn with Goethe’s poetry challenges stylistic consistency, despite the complex web of thematic links which underline the common philosophical threads of both texts. There is a typical Mahlerian paradox because the collision of styles makes his point. The first part of the symphony is archaic, universal and orderly. It depicts the idealised community, as in Wagner’s Meistersinger, by recreating the musical past. This is in stark contrast to Musil’s image of modern Vienna as an expression of dissonance and incoherence. Mahler’s movement posits something lost, but still longed for. The second part of the symphony assumes that the subject of the work has been ejected from this musical Eden, but now seeks to be restored to the community of souls. Mahler does not give an account of this fall from grace, although most German-speaking people familiar with the story of Faust would understand that, at the beginning of symphony’s second part, the protagonist has been cast into the abyss.

The structure of the second movement is much freer than the first, held together largely by its text, reflecting that this is an inner journey governed by Eros, not an encounter with orderliness. The Faust scene opens with an orchestral prelude evoking Nature’s mystery and wildness. The chorus paints an awesome scene of waving trees, rippling streams and mystical anchorites. Faust may have fallen, but it is into the primal depths of his unconscious, where reside the seeds of his renewal. Two songs follow; the Pater Ecstaticus sings of Love’s sustaining power and the Pater Profundus describes how Love is born out of the chaotic profusion of Nature, ending with a passionate plea for enlightenment. This music reminds us of Mahler’s insight that, despite Nature’s blind struggle for survival in its primitive forms, there is also an essential wisdom concealed within it, which steers living things towards the light. Carried upward by this power, human beings endure the rupture of ego-consciousness, leaving a psychic wound which only Nature can heal. We must connect with this intuitive wisdom if we are to be redeemed. Not surprisingly, this opening sequence of songs alludes to the Accende lumen sensibus section of the first movement; a plea is for guidance through the senses. God has given us the capacity to respond to Eros through feeling in order to make the instinctive connection which can reconcile us fully with Creation.

After this passage, which is really a slow movement, Faust’s liberated soul is transported by angels (choruses of women and boys) who exhort him to strive further. Only a recurrence of the Infirma nostri corporis theme of the first movement reminds Faust that the pain of earthly existence must be endured (Uns bleibt ein Erdenrest), before the joy of heaven can be bestowed. The arrival of Dr. Marianus heralds an ecstatic aria in praise of the Queen of Heaven, the Virgin Mary. The theme introduced by the violins over the harmonium at this point is amongst the most beautiful and simple Mahler ever conceived. It is a momentary glimpse of the beyond in Mahler’s heavenly key of E major, where a celestial choir is worshipping the Eternal-Feminine. What follows has the animation of a scherzo. Three penitent women (Magna Peccatrix, Mulier Samaritana, Maria Aegyptica) each in turn sing a biblical text as an invocation for forgiveness. Gretchen now appears as Una Poenitentium – a penitent, pleading on behalf of Faust. He is then redeemed and receives new and ever-lasting life. The Mater Gloriosa summons him to rise to the highest spheres, and Dr. Marianus guides him to the presence of the Chorus Mysticus, in what amounts to a symphonic finale of growing sweep and fluency. The final words of the symphony encapsulate the mystery of existence:

“Alles Vergängliche “All that is past

Ist nur ein Gleichnis; is but a likeness;

Das Unzulängliche, What has fallen short,

Hier wird’s Ereingnis; Here is achieved;

Das Unbeschreibliche, The indescribable,

Hier ist’s getan; Here is realised;

Das Ewig-Weibliche The Eternal-Feminine

Zieht uns hinan.” Draws us ever on.”

Worldly events are revealed as an intimation of the heavenly realm, and the masculine struggle for enlightenment is resolved in the attainment of its ultimate goal, Das Ewigweibliche – the Eternal Feminine, which is a gift generously given rather than won by striving. The Chorus Mysticus represents the spiritual community, bound in Eros, which Faust had abandoned, and which was so vividly depicted at the symphony’s opening.

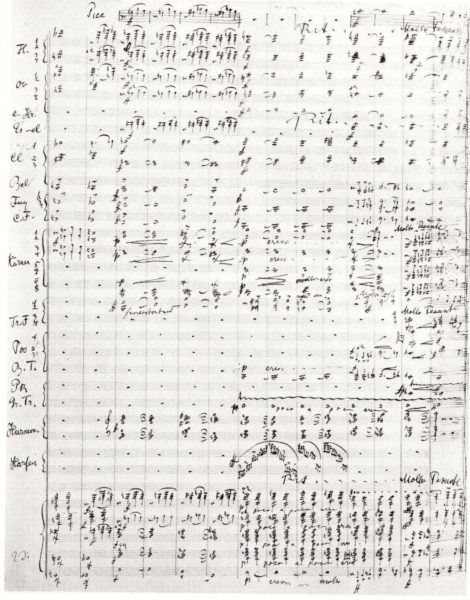

Mahler’s manuscript of the Chorus Mysticus

The Chorus Mysticus begins as a reverend whisper and ends in a glorious blaze of extra brass and full organ. Mahler wrote of this passage:

“Imagine the whole Universe beginning to ring and resound. There are no longer human voices, but planets and suns revolving in their orbits…”

The last bars reach out for transcendence. The final trumpet calls stretch more than an octave, leaping over the work’s massively resounding final E-flat major chord. The triad symbolises natural law; that which is harmonious with the Universe, and in these final bars, Faust’s soul is both reconciled to that law yet continues to reach beyond it. The return of the symphony’s opening material and home key reminds us how the struggle for transcendence began in the first place. The creative spirit, which derives from God, longs to return to Him. This means that humanity will always feel a profound dissatisfaction with the limitations of material existence, since the perfection for which humanity longs is not attainable in the constantly changing world of matter. Rather it is a gift bestowed by God which draws us beyond the mortal realm towards the eternal. Life, Mahler shows us, is born from an outpouring of divine Love, a boundlessly inventive energy that wants to flow back to its source. Man is thus both driven by and led towards the divine. It is by submitting to the creative power of heavenly inspiration that Man finds the strength and courage to complete his spiritual journey.

The Eighth Symphony is a maverick work, even by Mahler’s standards, considered by many to lack the depth of the trilogy that preceded it. It can seem as if the symphony regresses back to the Wunderhorn period of romantic dreaming. The music eschews the modernism of its predecessors and defies the contemporary mood of pessimism perpetuated by disgruntled moralists like Kraus and Schönberg. For some critics, this implies an empty idealisation; a loss of reality reflected in the work’s rushed composition and archaic gestures. Yet even a writer such as Thomas Mann, who was absorbed in portraying the decadence of German culture, was moved deeply by the music. The flawed figure of Faust was for Mann an image of the collective German soul. Mahler’s depiction of Faust’s redemption was thus a prophecy of a culture redeemed; a glimmer of hope where there was otherwise little cause for optimism.

The Faust story is ambiguous, because it hints that Man’s loss of soul is something unavoidable, even necessary for his spiritual development. He is a vulnerable creature, inevitably questioning the grounds of his existence. Man turns to God in doubt and shakes his fist, seeking to surpass his creator. This leads to a breach with the divine will and a loss of instinct. But according to Mahler and Goethe, Man will ultimately realise his need to reconnect with natural instinct, if he is not to become the devil’s plaything. By recognising his spiritual degeneration, Man can discover the healing powers of the Eternal-Feminine and so repair the wound of his ego-consciousness. Both artists portray the hubris of modern man as a phase of adolescence, which has to be endured before the spiritual light can return. The Eighth Symphony is therefore not a regression to a lost age of innocence, but a vision which reveals a destiny. It points to a spiritual maturity way ahead of Mahler’s own times and way ahead of our own.

©Peter Davison

April 2020

Peter Davis on was, for over twenty years, Artistic Consultant to The Bridgewater Hall, Manchester UK, where he created a high-quality classical music program, including the hall’s International Concert Series. He studied Musicology at Cambridge University, writing a thesis on the Nachtmusiken from Mahler’s Seventh Symphony, which led to an invitation to speak about his research at the 1989 Mahler Symposium in Paris. He also contributed to the Festschrift for Henri Louis de la Grange’s Seventieth birthday in 1994. In 2001, he edited Reviving the Muse, a book about the future of musical composition, and in 2010 published Wrestling with Angels about the life and work of Gustav Mahler to accompany The Bridgewater Hall’s acclaimed Centenary Symphony Cycle. He presented a paper at the 2016 Colorado Mahlerfest on the Seventh Symphony.

on was, for over twenty years, Artistic Consultant to The Bridgewater Hall, Manchester UK, where he created a high-quality classical music program, including the hall’s International Concert Series. He studied Musicology at Cambridge University, writing a thesis on the Nachtmusiken from Mahler’s Seventh Symphony, which led to an invitation to speak about his research at the 1989 Mahler Symposium in Paris. He also contributed to the Festschrift for Henri Louis de la Grange’s Seventieth birthday in 1994. In 2001, he edited Reviving the Muse, a book about the future of musical composition, and in 2010 published Wrestling with Angels about the life and work of Gustav Mahler to accompany The Bridgewater Hall’s acclaimed Centenary Symphony Cycle. He presented a paper at the 2016 Colorado Mahlerfest on the Seventh Symphony.

For the 2019 MahlerFest, Peter Davison explored the origins and influence of the melancholy hero in romantic literature and music, showing how this archetypal figure inspired Mahler’s Songs of a Wayfarer. The songs in turn provided themes and ideas for Mahler’s First Symphony, which seems largely to repudiate any sense of tragedy. From Shakespeare to Goethe, Schubert to Alban Berg, the misfit outsider, the jilted lover and the sensitive poet have been depicted as desperate and suicidal, representing the crisis of the individual facing the eternal questions of love, life and death. Can the romantic artist find sustainable answers or must he forever repeat cycles of joy and despair?